Joe Gans’s rise from orphaned and hard-working Baltimore Harbor oyster shucker to becoming the first African American to hold a world boxing title in 1902 is remarkable. He arguably was the first Black person to break the color barrier in any American professional sport. [2] Black and white Baltimorean press coverage of his story reveal the city’s social tensions at the turn of the twentieth century. Black Baltimoreans rallied around Gans. However, concerns about respectability meant the Black press did not favorably cover his story while he was alive. He faced harsh prejudice from powerful white Baltimoreans, who felt threatened by the race and gender implications of his boxing successes and tried to ban interracial matches. Gans’s story generated substantial white moral panic about race, gender, and class. He also established shared spaces for building middle- and upper-class Black and interracial community, most notably Baltimore’s Goldfield Hotel. Unfortunately, his death from tuberculosis provides further insights into early-twentieth century Black Baltimorean experiences with structural inequities causing this community to be hit disproportionately hard by the disease. In many ways, Joe Gans’s life is emblematic of Black Baltimorean struggle and achievement around the turn of the twentieth century.

Orphaned at age four and adopted by foster mother Maria Gans, Joe Gans left school at a young age to work shucking oysters in Fells Point’s Broadway Market. His birth father was a baseball player named Joseph Saifuss Butts, and Joe’s birth name was “Joseph Butts.” [3] As his boxing career took off, the media gave him the name “Joe Gans.” [4] He became an oyster shucker because his adoptive father worked at the Broadway fish market. The two got into the habit of heading to work together. Oyster shucking was a common form of labor for child workers in Baltimore Harbor during this period. Luckily for Gans, his boss at the fish market was a boxing coach named Caleb Bond. He helped the boy acquire his first pair of boxing gloves and set up initial matches for him to try out the sport. [5] For Black Baltimoreans, the primary gateway into organized boxing at this time was through a racially exploitative type of event called a “battle royal.” These typically placed four Black combatants in competition to be the last one standing. White Baltimoreans bet heavily on these matches and often hurled racial epithets at the hard-working combatants. The winner received a modest sum of money. [6] In many cases, the participants would be blindfolded. As scholars Colleen Aycock and Mark Scott emphasize, the anonymity caused by the blindfolds socially operated similarly to the blindfolding of victims at lynchings. [7] In both forms of racial violence, the Black body became an object of white public scrutiny and awe. While highly degrading, battle royals also provided an opportunity for the most talented boxers to get noticed by professional scouts.

Baltimore bookmaker and restauranteur Al Herford demonstrated his sharp eye for boxing talent when he approached Gans after watching him compete in a battle royal at Baltimore’s Monumental Theater. [8] He became Gans’s manager for most of his professional career, before Gans set out to manage himself in later years. While Baltimore’s Afro-American Ledger later described Herford as “his friend and manager,” this relationship was more exploitative than friendly from the start. [9] On numerous occasions, Herford manipulated Gans in efforts to monetize racial prejudice. For example, he forced Gans to intentionally lose at least two fights. It appears in these cases Herford either harnessed racial prejudice to convince people to take bets against Gans or exchanged intentional losses for commitments to participate in future high-money fights. [10] The most explicit way Herford monetized systemic racism was by intentionally seeking out interracial matches, even as Baltimorean and American societies became less tolerant of such contests. [11] Herford recognized that white spectators and bettors spent the most money at fights. He also knew that matches between Black fighters did not draw white crowds. Thus, he set out to arrange as many high-profile interracial clashes as possible for Gans. [12]

Reactions to Gans’s interracial matches and those of other famous Black boxers illuminate white moral panic over gender, race, and masculinity at the turn of the twentieth century. Historian Gail Bederman’s conceptualization of race and gender as historical phenomena will be used for the purposes of this study. For Bederman, gender “is a historical, ideological process. Through that process, individuals are positioned and position themselves.” Furthermore, “At any time in history, many contradictory ideas about manhood are available to explain what men are, how they ought to behave, and what sorts of powers and authorities they may claim, as men.” [13] Part of the appeal of interracial contests for white audiences was that a white man’s fighting victory over a Black man would validate normative white manhood. [14] However, when Black fighters such as Gans won these matches this exacerbated racial tensions. This perceived threat to public order was lessened by Gans always being classified as a lightweight boxer. Both Black and white society saw the heavier fighters as more representative of their race. [15] As Bederman writes, “Late Victorian culture had identified the powerful, large male body of the heavyweight prizefighter (and not the smaller bodies of the middleweight or welterweight) as the epitome of manhood.” [16] This was why Jack Johnson’s rise as the first African American heavyweight champion towards the end of Gans’s career generated such dramatic moral outrage in the white community. [17]

Reactions to Gans’s 1902 victory over Frank Erne demonstrate moral outrage over race and gender. Shortly after Gans claimed the world lightweight title from Erne in 1902, Baltimore Mayor Theodore Hayes cracked down on interracial boxing as part of his anti-Black social control agenda. [18] He was part of a newly empowered Democratic faction in Baltimore politics that sought to restrict Black Baltimorean rights. For Hayes and his supporters, interracial fights threatened the structural moral order of patriarchal white supremacy. Gans responded by writing a letter to the Baltimore Sun, pleading his case for the continued allowance of interracial boxing. He wrote, “I am a taxpayer here, and am, and have always been, a law-abiding citizen. I regard my means of gaining a livelihood as legitimate and honorable as any man’s.” Here he taps into the emphasis on male respectability prevalent in both Black and white Baltimorean society, presenting himself as a hard-working masculine contributor to civic culture. He also stressed how much Baltimore meant to him as his home, stating, “One thing that made the winning of the championship sweet was the thought that I could show my fellow townsmen that I was all that my admirers had credited me with being.” He then addressed the mayor’s proposal to only allow interracial matches including Black champions, deeming this unsportsmanlike since it would mean he could only participate in competition until losing his title. [19] Despite Gans’s plea, Hayes banned interracial boxing in Baltimore in January 1903. It remained banned when Robert McLane took over as mayor in July 1903. Race, gender, and respectability were still at the forefront for the new mayor, but he thought interracial matches would be good for preserving white manhood. This time promoters disagreed with the mayor and effectively re-banned the sport from 1904 to 1907, while making some exceptions for Gans. [20]

An important comparative for reactions to Gans’s 1902 title victory is Jack Johnson’s victory over Jim Jeffries at the end of that decade, in 1910. By this time, theaters regularly screened filmed versions of major prize fights. The number of people viewing major fights skyrocketed, which led to moral panic over race and gender implications of interracial fights. [21] In July 1910, shortly after the Johnson-Jeffries match, the Sun reported that according to Mayor J. Barry Mahool and Baltimore City Police Marshal Farnan, “Law-abiding people feel that it would be dangerous to public morals for the fight pictures to be shown here.” The implication of this moral threat is that the African American Johnson’s convincing defeat of the white man Jeffries provided an unacceptable refutation of white male supremacy. The Sun described the fight film as “Revolting.” Speaking to the enforceability of these concerns, “The Mayor said that he personally has no power to stop the exhibition, but if Marshal Farnan with his general police power should notify him that he considered the pictures against public morals he would prohibit them. Marshal Farnan decided to use his power in the way indicated by the Mayor.” Farnan elaborated on the moral threat, telling reporters, “It would be bad policy to allow pictures of a negro [sic] ‘smashing’ a white man to be shown.” Police Commissioner Baker Clotworthy went further, remarking: “Fights between a white man and a negro [sic], like the one held in Reno, should not be permitted under any circumstances at any place in the United States.” [22] Returning to Bederman’s conceptualization of race and gender, the public showing of a Black boxer overwhelmingly defeating a white boxer threatened the normative order that white Baltimore sought to construct.

The Black press in Baltimore and across the country also played a substantial moral regulatory role through its coverage of Joe Gans’s story, or lack thereof. In the first issue of the Baltimore Afro-American Ledger following Gans becoming the first African American boxing champion, no mention is made of the feat. [23] This evidence strengthens communications scholar Carrie Teresa’s argument that Gans “was effectively ignored in black press weeklies, which during his championship reign (1902 through 1908) were predominantly concerned with racial uplift.” For the Black press, boxing was not seen at contributing to Black respectability. However, Teresa also emphasizes that after Gans’s death in 1910 he was posthumously constructed as a moral hero. [24] Further evidence shows that this shift started even in the lead-up to his death, as it became publicly clear that his tuberculosis meant he would never fight again. Indeed, one newspaper Teresa does not cite is the Freeman, a national Black paper based in Indianapolis. In July 1909, more than a year before Gans’s passing but firmly within the timeframe of his debilitating illness, it published an article with the subtitle “Joe a Gentlemanly Fighting Man.” By emphasizing both gender and respectability, this article highlights the morally reformative work done by a certain version of Gans’s story, especially in contrast to the allegedly hedonistic lifestyle of Jack Johnson. [25] Looking back on his career, the Freeman reported, “he was a cool, fair, gentlemanly fighting man. He never took an unfair advantage. He fought like a man, matching brain against brain, and fist against fist.” [26] The implication of this additional evidence is that Teresa’s argument should be extended to include the entire period in which Gans was deemed no longer able to partake in the morally threatening act of boxing.

In sharp contrast to the lack of coverage of Gans’s career in the Black press during his peak years, the white-aimed and white-operated Baltimore Sun covered his career substantially. The paper’s racial prejudice is evident in its refusal to credit Gans with an authoritative victory over Erne in 1902, despite knocking Erne out “in the first round” and “with startling suddenness.” For the Sun, “The consensus of opinion by the [likely white] experts at the ringside was that the fight was altogether too short to successfully demonstrate the superiority of either man with the small gloves.” To the Sun’s credit, its reporting on his 1902 title acknowledged the respectable qualities that the Black press would later deem so admirable in Gans. This is clearest from the quote it featured about his humble reaction to the fight’s quick and decisive outcome: “‘Of course,’ he said, ‘I didn’t expect to win so quickly, but I believe the end would have been the same had the fight gone much further.’” [27] This statement is simultaneously humble and proud. It shows Gans as a gentleman who respects his opponent, while also firmly acknowledging his own public excellence. This is a very similar tone to the eulogizing of Gans’s life in Baltimore’s Afro-American Ledger shortly after his death. The Afro emphasized, “Gentlemanly in deportment, free from boasting, a stranger to brawls and fist fights—to sum it all up, he was a gentleman.” The Afro also stressed his wise investments, noting, “He was a brightminded, shrewd businessman.” [28] His primary investment was the Goldfield Hotel, which speaks to his commitment to building Black Baltimorean middle and upper-class community.

Gans’s investment in his Goldfield Hotel is the most direct financially impactful example of his consistent commitment to giving back to his home city of Baltimore. This was clear since his first world title victory in 1902, when he prioritized a celebratory parade through the city’s streets. This title fight itself was held in Fort Erie, Canada, but Gans made sure to return to Baltimore to share in the celebration. [29] The Sun reported on the festivities: “It seemed that every man or woman of color who was not sick in bed turned out yesterday to extend a welcome to Joe Gans, the champion lightweight pugilist of the world. . . . He bore with grace the honors thrust upon him, and smiled genially in response to the plaudits of the multitude.” [30] The creation of the Goldfield Hotel stemmed from a similar victory celebration. In 1906, Gans defeated Oscar “Battling Nelson” at a fight held in Goldfield, Nevada. He invested his winnings from this bout in the Goldfield Hotel, hence the name. [31] It opened by the end of 1907, catering to middle- and upper-class Black Baltimoreans but warmly welcoming white patrons as well. [32] By 1909, the Sun lauded the Goldfield as “the resort of all the colored sports of Baltimore.” [33] It became a hub and launching pad for Black Baltimorean culture. For example, Gans employed future nationally renowned Black Baltimorean musician Eubie Blake as his house pianist. [34]

Beyond the Goldfield, Gans also gave back to Black Baltimore by leading and operating one of the city’s first successful Black quasi-professional baseball teams. This was personally significant to him since his Baltimorean birth father was a professional baseball player. [35] Gans initially played and managed for the Baltimore Giants of the Colored Southern Ball League, joining the team when not otherwise occupied by boxing. Then he founded his own team, which was known as “Joe Gans’s Nine” and was later renamed the Baltimore Giants to honor the previously extant team. [36] In his work on the Baltimore Black Sox, the professional Black baseball team that emerged in Baltimore after Gans’s death, historian Bernard McKenna argues Gans “made the later success of the Black Sox possible.” [37] Not only was Gans continuing his birth father’s Black Baltimorean baseball legacy, he was also advancing African American professional sports in the region. He additionally invested in these pursuits by placing substantial bets on his team’s games to further entice opponents to travel to Baltimore and play against the squad. [38]

The most tragic way that Gans’s story embodies the Black Baltimorean experience in the late-twentieth century is his fatal struggle with tuberculosis. As the disease spread across the country in this period, it hit Black populations disproportionately hard. Structural economic inequities meant that Black Baltimorean communities tended to be more crowded and less financially endowed than their white counterparts. Crowded conditions combined with a relative lack of funds for elaborate experimental treatments to disproportionately impact Black Baltimoreans. Medical science at the time lacked a clear cure for tuberculosis. Those who could afford it, like Gans, were encouraged to take a vacation to the mountains and use the fresh air to heal their lungs. [39] By contrast, industrial Baltimore was notorious for air pollution, which was especially bad in the working-class neighborhoods where most Black residents lived. [40] Baltimore’s tuberculosis situation was closely monitored due to the proximity of one of the nation’s most advanced medical institutions: Johns Hopkins University. Detailed data reveals the disease’s uneven racial impacts. As the Sun reported, the “Figures Are Startling.” According to a 1904 Hopkins study, “111 deaths of whites out of every 1,000 were caused by tuberculosis, while 151 out of every 1,000 deaths among the colored population were due to the same disease.” [41] Such data likely contributed to Gans’s resistance to media acknowledgement of his diagnosis. When boxing referee Charley White told the media that Gans had tuberculosis and “may never again be seen in the ring” in March 1909, Gans’s wife was also quoted as publicly denying the claim and citing by name the doctor who asserted Gans did not have the disease. [42] He continued to compete as he battled tuberculosis, but was clearly not at his best. [43]

Joe Gans’s story illuminates how race, gender, and class shaped life and popular culture in turn of the twentieth century Baltimore. His ability to break into the field of professional boxing despite being raised in poverty and being discriminated against for being Black shows his resilience. His success was reflected in the economic freedom he carved out for himself despite these barriers. When he became the first African American boxing champion, he proved Black excellence on one of the largest sporting stages. While he surely provides an exceptional case, his life also speaks to what it meant to be Black in Baltimore around the turn of the twentieth century. When the Black press chose not to cover his fights to protect standards of middle-class respectability, Gans likely felt disrespected. If not then, he clearly felt disrespected when city officials attempted to ban interracial boxing starting in 1902. He emphasized in his responding letter to the Sun that he believed his profession was just as respectable as any other and should be treated as such. [44] It was not until after his death that Gans featured prominently in the Black press. This coverage did treat him respectfully but was aimed more at the way he approached the sport of boxing than his professional accomplishments. His commitment to sportsmanship and the normative behavior of a gentleman was deemed an admirable example for African Americans to follow. [45] By establishing and investing in the Goldfield Hotel in Baltimore’s Jonestown neighborhood, he left a tangible legacy of commitment to his home city. It was a place for Black Baltimoreans to gather and enjoy themselves together, along with the also welcome white Baltimoreans. Gans always made clear his love for Baltimore. In many ways, he embodied Baltimore. He deserves a larger place in the city’s public memory.

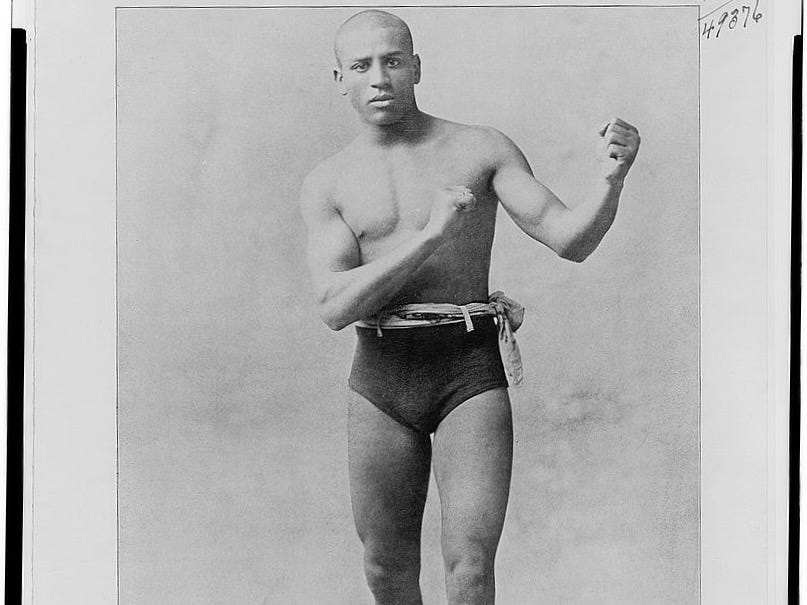

[1] Richard K. Fox, “Joe Gans, of Baltimore,” photograph (location unknown, c. 1898), public domain, https://www.loc.gov/item/96515727/.

[2] William Gildea, “‘For a White Boy’s Chance in the World’: Joe Gans, Baltimore’s Forgotten Fighter,” in Baltimore Sports: Stories from Charm City, ed. Daniel A. Nathan (Fayetteville: The University of Arkansas Press, 2016), 42, https://archive.org/details/baltimoresportss0000unse.

[3] Gildea, “For a White Boy’s Chance in the World,” 40.

[4] Colleen Aycock and Mark Scott, Joe Gans: A Biography of the First African American World Boxing Champion (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2008), 14, https://archive.org/details/joegansbiography00ayco.

[5] Gildea, “For a White Boy’s Chance in the World,” 40-42.

[6] Louis Moore, I Fight for a Living: Boxing and the Battle for Black Manhood, 1880-1915 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2017), 10, Kindle edition.

[7] Aycock and Scott, Joe Gans, 12.

[8] Aycock and Scott, Joe Gans, 17.

[9] “GAME FIGHTER LOSES OUT IN HIS FINAL BOUT,” The Afro-American Ledger (Baltimore, MD), August 13, 1910, 5, https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=Sx4mAAAAIBAJ.

[10] Moore, I Fight for a Living, 89.

[11] See “‘STOP IT,’ SAYS MAYOR,” Sun (Baltimore, MD), July 6, 1910, 14, https://www.newspapers.com/image/371148839/; Jeffrey T. Sammons, Beyond the Ring: The Role of Boxing in American Society (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988), 34, https://archive.org/details/beyondringroleof0000samm.

[12] Gildea, “For a White Boy’s Chance in the World,” 42.

[13] Gail Bederman, Manliness & Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880-1917 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1995), 7, https://archive.org/details/manlinessciviliz0000bede.

[14] Moore, I Fight for a Living, 16.

[15] Sammons, Beyond the Ring, 34.

[16] Bederman, Manliness & Civilization, 8.

[17] For more on Jack Johnson’s story, see Theresa Runstedtler, Jack Johnson, Rebel Sojourner: Boxing in the Shadow of the Global Color Line (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012).

[18] Moore, I Fight for a Living, 142-143.

[19] “WHAT JOE GANS THINKS OF IT,” Sun (Baltimore, MD), December 14, 1902, 6, https://www.newspapers.com/image/371673084/.

[20] Moore, I Fight for a Living, 144-145.

[21] Dan Streible, “A History of the Boxing Film, 1894-1915: Social Control and Social Reform in the Progressive Era,” Film History 3, no. 3 (1989): 247, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3814980.

[22] “‘STOP IT,’ SAYS MAYOR,” Sun, July 6, 1910, 14.

[23] “PUBLISHED EVERY SATURDAY IN THE INTEREST OF THE RACE,” The Afro-American Ledger (Baltimore, MD), May 17, 1902, 1-8, https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=wVUmAAAAIBAJ.

[24] Carrie Teresa, Looking at the Stars: Black Celebrity Journalism in Jim Crow America (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019), 163, Kindle edition.

[25] Teresa, Looking at the Stars, 175.

[26] “JOE GANS HAS QUICKEST KNOCKOUT RECORD,” The Freeman (Indianapolis, IN), July 31, 1909, 7, https://books.google.com/books?id=4KsnAAAAIBAJ.

[27] “GANS IN QUICK TIME,” Sun (Baltimore, MD), May 13, 1902, 6, https://www.newspapers.com/image/370565726/.

[28] “GAME FIGHTER LOSES OUT IN HIS FINAL BOUT,” Afro-American (Baltimore, MD), August 13, 1910, 5, https://books.google.com/books?id=Sx4mAAAAIBAJ.

[29] Moore, I Fight for a Living, 44.

[30] “TURN-OUT FOR GANS,” Sun (Baltimore, MD), May 20, 1902, 6, https://www.newspapers.com/image/370569454/.

[31] “LANDMARKS OF OLD BALTIMORE IN PLACID ‘OLD TOWN,’” Sun (Baltimore, MD), June 20, 1909, 13, https://www.newspapers.com/image/371300176/; Richard Carlin and Ken Bloom, Eubie Blake: Rags, Rhythm, and Race (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), 34-35, Kindle edition.

[32] Aycock and Scott, Joe Gans, 191.

[33] “LANDMARKS OF OLD BALTIMORE,” Sun, June 20, 1909, 13.

[34] Carlin and Bloom, Eubie Blake, 32-33.

[35] Aycock and Scott, Joe Gans, 23.

[36] Bernard McKenna, The Baltimore Black Sox: A Negro Leagues History, 1913-1936 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2020), 15, Kindle edition.

[37] McKenna, The Baltimore Black Sox, 39.

[38] “The Philadelphia Giants Arrive,” Baltimore American, July 18, 1901, 12, https://books.google.com/books?id=aNxdAAAAIBAJ;

[39] Aycock and Scott, Joe Gans, 186-187.

[40] Dennis Anthony Doster, “‘To Strike for Right, To Strike With Might’: African Americans and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Baltimore, 1910-1930” (PhD diss., University of Maryland, College Park, 2015), 241, https://www.proquest.com/openview/3a77815727d27f7b3fe129699f1e724f/1.

[41] “FIGURE ON WHITE DEATH,” Sun (Baltimore, MD), January 14, 1904, 7, https://www.newspapers.com/image/372492283/.

[42] “Joe Gans in Poor Health,” New York Times, March 30, 1909, 10, https://nyti.ms/3s1FHtd; “GANS’ RING DAYS OVER,” Sun (Baltimore, MD), March 30, 1909, 10, https://www.newspapers.com/image/372108473/.

[43] Teresa, Looking at the Stars, 43.

[44] “WHAT JOE GANS THINKS OF IT,” Sun, December 14, 1902, 6.

[45] “GAME FIGHTER LOSES OUT,” Afro-American, August 13, 1910, 5.