In September 1910, African American businessperson and Baltimore resident Samuel L. Burton sued his birthplace of Onancock, Virginia, in what Baltimore’s Afro-American Ledger described as “One of the most unique cases in the history of race riots.” [2] National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) publication The Crisis reported that, “The case came to a final trial on January 14, 1913, and Burton was awarded $3,500 damages.” Emphasizing the role of Burton’s attorney W. Ashbie Hawkins, one of Baltimore’s first African American lawyers, the report continued: “The verdict is much too small, but any verdict was a triumph and W. Ashbie Hawkins deserves great credit.” [3] The case regarded the white lynch mob that attempted to murder Burton in his hometown in 1907. These events drove his move to Baltimore. As the Afro reported, he felt he could not return to Onancock “on account of threats to do him bodily harm.” [4] A primary motivator for this racial violence was the white community’s knowledge that Burton encouraged local Black people to demand fairer wages from white employers. [5] He also owned a successful grocery store in Onancock that he said made $10,000 per year, but it was burned to the ground by white residents during the 1907 riot. [6] He worked as a store clerk upon his arrival in Baltimore, then advanced economically by investing the damages won in court in a clothing store. [7] By January 1921, The Crisis listed Burton as one of the notable African American businesspeople in the United States: “Samuel L. Burton, a Negro in Baltimore, Md., started a clothing business in 1917; his first year’s business amounted to $17,000; in 1918, $35,000; 1919, $45,000; for 1920 his business is estimated at $60,000.” [8] An examination of this remarkable Baltimore success story emerging from near-fatal white Virginian racial violence illuminates how Burton harnessed Baltimore-specific circumstances to mount a heroic socio-economic comeback.

Samuel L. Burton was born in Onancock, Accomack County, Virginia, in 1870. [9] His birth into freedom was a major life accomplishment for his parents James and Maria Burton, as it appears their previous children were born into slavery. In the 1890s, Samuel L. Burton joined one of the first generations of African Americans from formerly enslaved families to earn a college degree. He then became a public school teacher in Accomack County before opening his own grocery store in Onancock. [10] As he advanced his career, Burton invested in local real estate and served leadership roles in Black social and agricultural organizations. [11] He employed at least three African Americans at his grocery store. [12] In addition to his work advocating for fairer wages for Black workers, he also leapt to the defense of one of his Black employees during a debt-related conflict with a local white person. [13] This employee was named Sylvanus Conquest and was an African American former farm laborer who worked as a clerk at Burton’s store. Conquest’s upward mobility shows that Burton leveraged his entrepreneurial successes to economically advance other members of the local Black community. [14]

The Onancock Race Riot started on August 10, 1907, when a police constable attempted to seize a horse tied up outside of Burton’s store. He justified the seizure as a means of reclaiming a debt owed by Conquest to local white man John M. Fosque. [15] When Conquest intervened and said that the horse in fact belonged to his employer, a conflict ensued. Burton objected to the constable’s treatment of his employee and was arrested for “interfering with an officer.” [16] In an unrelated nearby incident, a Black person named John Topping was shot in the back. Authorities claimed the shots were aimed at a nearby horse-drawn carriage. Local African American Braden Short was driving two men around in this carriage. Short claimed he saw a light on in Burton’s store shortly before the shooting took place “twenty-five or thirty feet” down the road. [17] This eyewitness claim of a light in the store and the allegedly correlated shooting provided the purported evidence against Burton and Conquest in the murder case that followed. White residents of Onancock heard rumors of Burton and Conquest’s conflict with the constable and decided it was connected to the nearby shooting. Trying to take violence into their own hands, they armed themselves and set out searching for victims. They ran into and attacked Burton’s business partner James D. Uzzle, who shot at and wounded one of the attackers in self-defense. This aggravated the mob further. As historian Blair L.M. Kelley points out, Uzzle, Burton, and Conquest then hid “in the wilderness, just as enslaved people trying to avoid capture had done in prior generations.” [18] The mob roamed the area with lynching on their minds. After a week, Uzzle, Burton, and Conquest all emerged and surrendered themselves to the authorities. [19]

Local officials crafted a story linking Burton and Conquest to the killing of Topping, claiming that they mistook him for Fosque and shot him. [20] In the ensuing court case, the Circuit Court of Accomac County indicted Burton and Conquest for the murder of Topping. Both were sentenced to ten years in a penitentiary. [21] Given the lack of evidence, it is likely that racial prejudice played a role in this sentencing. The accused appealed the case, which made its way to the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals. In its decision, this court ruled, “that the evidence is insufficient to show that the shots which killed Topping were fired by either Burton or Conquest.” The judge emphasized: “There is not a scintilla of evidence that either Burton or Conquest countenanced, encouraged, counselled, aided, abetted, advised or consented to the firing upon the hack [carriage].” [22] The court cited the defense's evidence showing that Burton’s acquaintance Mr. J. C. Westcott contacted him around the time of the shooting, warning him to leave town to evade the lynch mob. Further testimony showed Burton closed his store in response, visited a local Black woman’s home where he often ate meals, then hid in the woods. [23] The lower court rendered a guilty verdict without significantly considering evidence presented by the defense. Once this evidence was seriously examined, the appeals court reversed this decision. The case was then “remanded to the Corporation Court of the city of Norfolk,” which confirmed the reversal and freed the accused. [24]

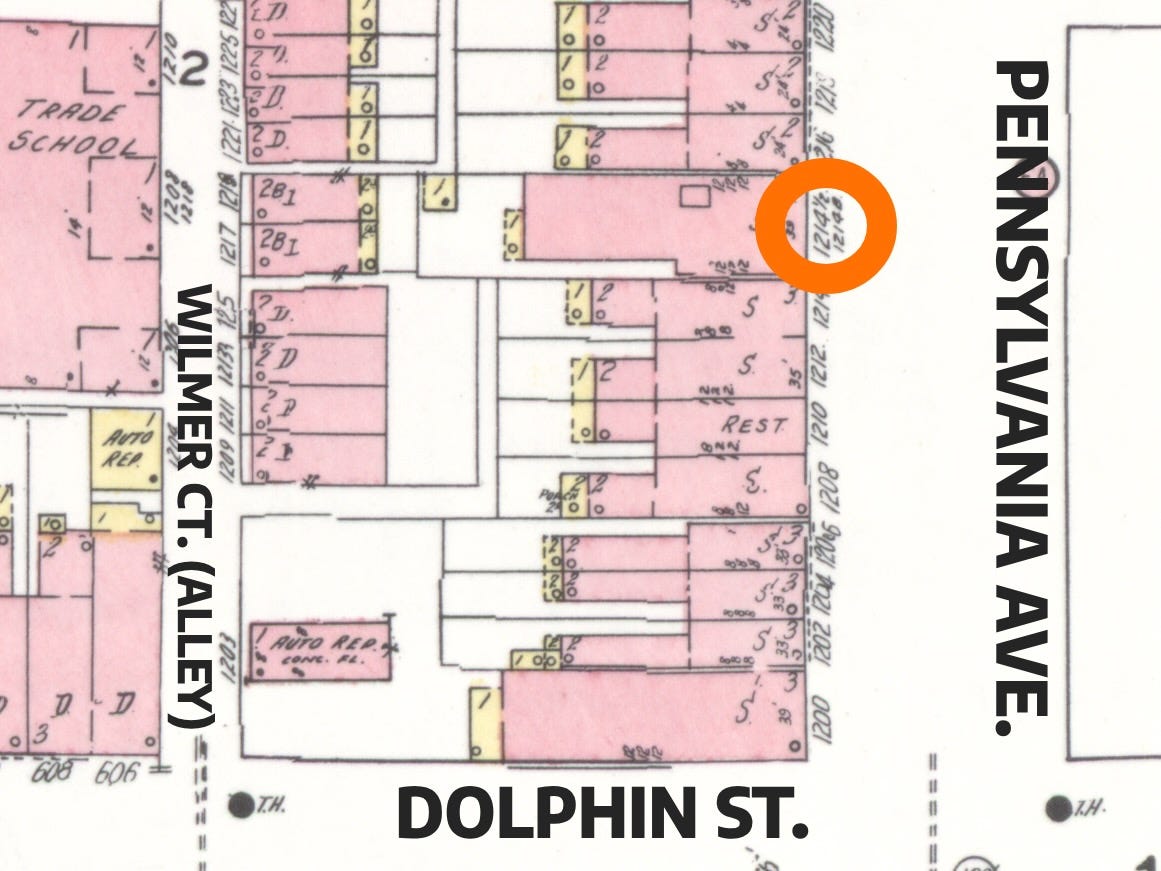

When Burton moved to Baltimore and decided to press charges against the town of Onancock, he very wisely chose W. Ashbie Hawkins to represent him. Burton’s choice of Baltimore as his new home enabled this astute hire, since the city was a national hub for the emergent Black attorney professional class. [25] In this way, the newcomer to the city Burton harnessed decades of hard-earned Black Baltimorean progress in business and civil rights. He leveraged Baltimore’s historic Black excellence to achieve justice against the town that tried to lynch him and the local officials who tried to frame him for a crime he did not commit. Black Baltimorean achievement also empowered Burton’s rise as a successful entrepreneur in the city after his victorious lawsuit. Once his clothing store achieved substantial success, he moved into a more prominent location on Pennsylvania Avenue, along a historically Black stretch of businesses (Figure 1). By building a profitable business in this culturally significant location, he added to Black Baltimorean community pride.

Burton’s attorney W. Ashbie Hawkins began his legal education at the University of Maryland Law School, then finished it at Howard University in Washington, D.C. This school change was not by choice. Shortly after Harry Sythe Cummings and Charles W. Johnson became the first Black students to graduate from the University of Maryland Law School in 1889, white student backlash led the school to reimpose its prior policy of racial segregation. This policy change happened while Hawkins and his Black classmate James L. Dozier were midway through the program. They were forced to continue their education elsewhere and both transferred to Howard. In 1892, they both joined the Baltimore bar. [26] Burton’s case was one of many Hawkins took on in his first decade as a practicing attorney. After winning this case, Hawkins went on to become one of the initial presidents of the Baltimore NAACP in 1916. [27] By 1926, the Afro-American published an article reflecting on Hawkins’s career up until that point. Emphasizing both his legal successes and community involvement, the Afro proclaimed: “There is no one in Baltimore more prominently connected with its history and growth than lawyer W. Ashbie Hawkins. For more than 30 years Mr. Hawkins has championed the cause of the colored people of Maryland in some of the bitterest fought battles in its history . . . [and] in the majority of cases emerged successful.” [28] Burton’s case was in very capable hands.

Hawkins and Burton shared numerous commonalities, which likely added to their already promising chances of success in court. For example, they both strongly advocated higher salaries for African Americans. Hawkins was a member of Baltimore’s Defense League, described succinctly by historian Hayward Farrar as “a local black civic group agitating for equal pay.” [29] Similarly, Burton’s advocacy of better wages for Black people in Onancock was one of the primary causes of the white rage that threatened to take his life. He focused this work particularly on the cause of Black farm laborers, whom he deemed especially susceptible to wage exploitation. Another commonality for Burton and Hawkins was their involvement with various community organizations. In Onancock, Burton was the head of the local Black Masons and Odd Fellows. He also volunteered his time for the regional Black agricultural fair association. [30] He continued this community leadership work in Baltimore later in life, serving a directorial role for “The Colored Business Men’s Exchange.” [31] Hawkins was also a Mason and was a member of the Knights of Pythias, “the first fraternal organization in the United States to be chartered through an Act of Congress.” [32] Both Burton and Hawkins demonstrated strong commitment to building Black community throughout their professional and personal pursuits.

In Burton’s suit, Hawkins sought damages from the town of Onancock itself along with the mayor and four other citizens. Unfortunately, as The Crisis reported, he “was unable to get witnesses from there [Onancock] to testify, as most of the colored people were intimidated.” [33] This detail draws crucial attention to the African Americans directly impacted by the 1907 race riot who, unlike Burton, never received positive outcomes from the case. Kelley importantly emphasizes that Burton’s “survival and success prompt the question of what happened to the other fifty Black families banished from Accomack County in the wake of the riot. They did not sue for the value of the land and property they lost . . . There would be no justice for the rest of those forced out of Accomack for their expressions of Black advocacy, or merely for their prosperity.” [34] The prosperous ending to Burton’s story must not detract from the financial and lived suffering these other Black people faced due to white mass violence and structural racism. The Afro reflected on Burton’s case in 1926 as embodying Hawkins’s excellence and Burton’s success as a “well known department store owner of this city.” Other Black Virginians uprooted in 1907 were written out of this narrative. [35] Burton emerged triumphant, but the Onancock Black community felt harmful reverberations of the race riot for generations.

Samuel L. Burton won a remarkable courtroom victory in January 1913, receiving $3,500 in damages from the town that attacked him in a 1907 Virginian race riot. White residents sought to lynch him for encouraging his Black peers to seek better wages and for his falsely alleged connection to a shooting. The mob’s failure to achieve its murderous goals related more to the State of Virginia’s concerns about lynching being bad press than anything else. The accused Burton, Uzzle, and Conquest received a militia escort out of the town all the way to Norfolk, where they faced trial. [36] When Burton moved to Baltimore shortly thereafter, this city provided him with great legal and professional opportunities. By hiring W. Ashbie Hawkins, the city’s leading Black lawyer, he greatly increased his chances of success. Hawkins overcame formidable obstacles to earn his professional prominence, including race-based expulsion from the University of Maryland Law School. He and other members of Baltimore’s growing Black professional class also established a welcoming business community for Burton. While his previous store in Onancock faced substantial local white prejudice and violence, Baltimorean civil rights gains gave his Baltimore business a measure of protection. He made sure to give back to this Baltimore community that brought him post-riot life success, contributing greatly to community organizations. This story demonstrates that in the early-twentieth century United States, relative Black liberation in Baltimore was the exception rather than the rule, especially in the South. Yet, this exceptionality must not detract from the immense empowerment, struggle, solidarity, and possibility in Black Baltimorean histories.

[1] Sanborn Map Company, “Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Baltimore, Independent Cities, Maryland,” vol. 2, 1914, Library of Congress Geography and Map Division (Washington, D.C.), public domain, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3844bm.g3844bm_g03573195202; “Burton Reorganizes,” The Afro-American (Baltimore, MD), August 8, 1825, 18, https://books.google.com.do/books?id=aDYmAAAAIBAJ.

[2] “ENTERS SUIT AGAINST ONANCOCK,” The Afro-American Ledger (Baltimore, MD), September 17, 1910, 5, https://books.google.com.do/books?id=USEmAAAAIBAJ&lpg.

[3] “COURTS,” The Crisis 5, no. 5 (March 1913): 222, https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:520531/PDF/.

[4] “ENTERS SUIT AGAINST ONANCOCK,” The Afro-American Ledger (Baltimore, MD), September 17, 1910, 5, https://books.google.com.do/books?id=USEmAAAAIBAJ&lpg.

[5] Brooks Miles Barnes, “The Onancock Race Riot of 1907,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 92, no. 3 (July 1984): 338, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4248730.

[6] “BURTON ASKS DAMAGES,” The Afro-American Ledger (Baltimore, MD), September 24, 1910, 3, https://books.google.com.do/books?id=UiEmAAAAIBAJ.

[7] Blair L.M. Kelley, Black Folk: The Roots of the Black Working Class (New York: Liveright, 2023), 172, Kindle edition.

[8] “INDUSTRY,” The Crisis 21, no. 3 (January 1921): 131, https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:513420/PDF/.

[9] Ancestry.com, 1910 United States Federal Census [database on-line], Ancestry.com Operations Inc., 2006, original data: National Archives (Washington, D.C.), Year: 1910; Census Place: Baltimore Ward 14, Baltimore (Independent City), Maryland; Roll: T624_557; Page: 14a; Enumeration District: 0231; FHL microfilm: 1374570, https://www.ancestry.com/sharing/7183840?mark=7b22746f6b656e223a22787535696753355a3158746f364254352b4b7079307579333339767a447166366b46764779396d307a52413d222c22746f6b656e5f76657273696f6e223a225632227d.

[10] Kelley, Black Folk, 167.

[11] Barnes, “The Onancock Race Riot of 1907,” 338.

[12] Burton and Conquest v. Com'th, 108 VA. (1908), 896, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/chi.67221972.

[13] Kelley, Black Folk, 171.

[14] Kelley, Black Folk, 171.

[15] Burton and Conquest v. Com'th, 108 VA. (1908), 895.

[16] “COURTS,” The Crisis (March 1913), 222.

[17] Burton and Conquest v. Com'th, 108 VA. (1908), 894-895.

[18] Kelley, Black Folk, 171.

[19] Barnes, “The Onancock Race Riot of 1907,” 346.

[20] Barnes, “The Onancock Race Riot of 1907,” 340.

[21] Burton and Conquest v. Com'th, 108 VA. (1908), 893.

[22] Burton and Conquest v. Com'th, 108 VA. (1908), 900-901.

[23] Burton and Conquest v. Com'th, 108 VA. (1908), 896.

[24] Burton and Conquest v. Com'th, 108 VA. (1908), 901; “COURTS,” The Crisis (March 1913), 222.

[25] David S. Bogen, “The Forgotten Era,” Maryland Bar Journal 19, no. 4 (May 1986): 11-12, https://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/fac_pubs/642.

[26] Bogen, “The Forgotten Era,” 11.

[27] Lee Sartain, Borders of Equality: The NAACP and the Baltimore Civil Rights Struggle, 1914-1970 (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2013), 16, Kindle edition.

[28] “A Champion of the People’s Rights,” The Afro-American (Baltimore, MD), February 27, 1926, 13, https://books.google.com/books?id=YBomAAAAIBAJ&lpg=PA13.

[29] Hayward Farrar, The Baltimore Afro-American, 1892-1950 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1998), 33, https://archive.org/details/baltimoreafroame0000farr.

[30] Barnes, “The Onancock Race Riot of 1907,” 338.

[31] “Burton for Exposition,” The Afro-American (Baltimore, MD), June 29, 1923, 14, https://books.google.com.do/books?id=KysmAAAAIBAJ.

[32] “Knights of Pythias,” National Museum of American History, accessed October 22, 2023, https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_324730; Sartain, Borders of Equality, 16.

[33] “COURTS,” The Crisis (March 1913), 222.

[34] Kelley, Black Folk, 173-174.

[35] “A Champion of the People’s Rights,” The Afro-American, February 27, 1926, 13.

[36] Kelley, Black Folk, 172.