CONTENT WARNING: white supremacist violence

Sixteen-year-old Black Baltimorean Nia Redmon tried to go to school on April 5, 1963. Each school day she took the bus from her East Baltimore home to Northern High School, as part of bus-based school integration efforts. That morning, “the principal was on the [school] lawn and the police and they didn’t let the children get off the busses [sic].” Nia looked across the street and saw “a big cross that had been burnt out the night before.” She later learned, “the head of the Ku Klux Klan for the state of Maryland’s son went to that school, and the next day after Dr. King’s assassination they came there and put that large cross on the lawn and burnt that.” [2] This anecdote provides a glimpse into a particular Black Baltimorean experience of spring 1968, one prominently featuring white supremacist violence and racial terror directed at Black children. This article is the third part of a four-part series on “Revisiting the ‘Baltimore ‘68’ Oral History Interviews. As mentioned in prior iterations, this series groups interviews according to their website pages to reflect how viewers are likely to receive the content. This third group contains a remarkably large proportion of Black Baltimorean interviewees, as well as a substantial number of white interviewees demonstrating solidarity with Black Baltimore. The focus here will be on this group of Baltimoreans and their experiences of the societal response to the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. These interviewees provide important corrective to traditional portrayals of the April 1968 Baltimore unrest as unjustified and harmful. They stress the motivations and emotions behind the unrest and reflect on its real impact on Black Baltimoreans.

The assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had a deep emotional impact on Black Baltimoreans. Dorothy Hurst, who was 23 years old in 1968, powerfully embodied this aspect with her emotional experience reflecting on these events. The interviewer asked the recurring question, “What do you remember about the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.?” Hurst responded, “Ahhhhh, it was horrible. Ummmm, I felt betrayed.” The transcriber then noted in parentheses, “Pause: She starts crying.” [3] This emotion is an important place to start for this interview group, because it demonstrates how for some Black Baltimoreans Dr. King’s assassination felt like both a personal and a collective attack. Relatedly, Black interviewee Frieda Halderson emphasized personal fear for herself and her loved ones. She shared, “During the time you just, you had a whole lot of fear in you and then the… fear of your family, your total family, and the safety of your own family.” [4] Another Black Baltimorean interviewee, Yvonne Hardy-Phillips, connected the spring 1968 unrest to very real emotional reactions to past and present prejudice. She recalled, “So that rioting, some of that was born out of real anger over past slights and injustices.” [5] Some white interviewees also saw these events as directly resulting from harms done to the Black community.

White Baltimorean interviewees Francis J. Knott and Father Richard Lawrence both deemed the violence and looting of spring 1968 to be significantly targeted. They pushed back against misconceptions that the looting and burning of local businesses was indiscriminate. As co-founder of the student organization Loyola Students for Social Action, Knott had many connections to Black communities in the city. Reflecting on the property damage, he noted, “what was striking to me was that, although it may have started randomly, once it [got] going it was clear there were certain targets that I would say were retribution targets.” He laid out three major targets: “the corner dry cleaner, the corner grocery store and liquor stores in that order.” [6] Father Lawrence also emphasized corner stores and liquor stores as targets given how they harmed Black communities through disreputable “unlicensed check cashing.” [7] Knott argued that businesses were taking “lay a way” payments, then selling customers’ laundry if the payment was not made within one month. They sold the laundry if any less than one hundred percent of the payment was made, providing no compensation to the rightful owner. Similarly, liquor stores provided one of the only places for Baltimoreans without bank accounts to cash checks. They took advantage of this position by taking a large cut of all checks. Additionally, corner grocery stores sold items on credit then charged ridiculously high interest. [8] Father Lawrence identified another type of targeted business, those who sold illicit drugs to Black youth. He discussed a bar owner who was selling narcotics as a neighborhood side-hustle. He memorably stated, “He was selling dope to their kids, and he was burned to the ground, African American or not, he was burned to the ground, that was score settling time.” [9] From these perspectives it is clear at least some of the violence involved in the 1968 unrest was targeted against those causing harm to Black communities.

This group also includes an interviewee who claimed to be in the middle of the unrest as an active participant, Black Baltimorean Herbert Hardrick. He was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1967 but in spring 1968 was temporarily on leave and back home in Baltimore. [10] When asked if he watched coverage of the unrest, Hardrick responded, “Yeah, we looked at bits and pieces of it, but mainly we was out there in it.” [11] He also used his army uniform as a means of manipulating state officials, thus minimizing obstacles to looting. He recalled, “So what I would do, I’d go in and put my army fatigues on and I could walk anywhere I wanted to walk because I looked like one of the National Guards and I didn’t have to worry about that.” It appears he did not mind being seen engaging in the unrest while in uniform. When the interviewer asked, “So what were you doing when you were in your uniform?” He responded, “Looting, stealing, doing what I could do.” [12] Hardrick also illuminates how a participant in the unrest viewed its legacies post-1968. Indeed, he reflected that Baltimore communities lost “the cohesiveness that used to be in the neighborhoods, it was like every man for himself.” [13] While he did not mention targeted looting in his interview, he did emphasize the lack of community cohesion. Both the targeted looting and Hardwick’s recollections of post-1968 impacts are manifestations of a lack of community care.

Some interviewees recalled the 1968 unrest as positively impacting Black Baltimore moving forward. Black Baltimorean Harold L. Knight was sixteen years old at the time and living in East Baltimore, right in the heart of the unrest. [14] He felt that the unrest brought communities together in solidarity. He noted, “One of the things that did come out of it that’s good was that it enabled community-based organizations to be fortified. I saw that [there were] many people who came together who would not have done so maybe if the riots had not occurred.” [15] Black Baltimorean Lillie Hyman, who was also a teenager at the time, felt the unrest made Black communities more militant. She believed that post-1968 Black Baltimoreans were more likely to defend the interests of themselves and their communities through violence. [16] For some interviewees, including Hyman herself, this militancy was an unfortunate departure from Dr. King’s non-violent philosophy. [17] However, it was also important to the growth of the Black Power movement.

Two white interviewees in this group also focused on what they deemed to be positive outcomes of the unrest. Annie Perkins was thirty-one years old in 1968 and considered herself an ally of the civil rights movement. [18] She claimed that spring 1968 caused some white Baltimoreans to rethink their approach to race relations and try to find ways to build interracial community cohesion. Most specifically, she recalled “a huge community meeting at Grace Methodist in North Baltimore” where “a number of the black leaders came and spoke.” She continued, “There were lots of people who cared to come to something like that an[d] to think about what could be done.” She said, “The main message was to reform your own institutions.” While she noted most attendees were surprised by this conclusion, it remains quite profound today for how white Americans can work towards better race relations. [19] White interviewee Ted Lewis also focused on positive outcomes for Black Baltimore, but in a more problematic light. He embodied a racial uplift perspective, reflecting an outlook that seems to ignore systemic factors. When asked how Baltimore changed after the unrest, he responded, “I think a lot of blacks have improved their education and have advanced and become part of the society rather than oppressed from the society. We still have a large number that resent the white person they feel that they’re taking advantage of them.” [20] In crediting individual Black people with improving their individual situations by excelling in mainstream capitalist institutions, Lewis overlooks continued structural injustices.

Lewis was also one of a few white interviewees in this group with businesses irreparably harmed by the events of spring 1968. Another example is the Pats family, who owned a pharmacy in Baltimore City in 1968. They lived in the housing quarters directly above the store. [21] Regarding the burning and looting, Pats family member Sharon Singer recalled, “I remember it, I lived it, so I do remember it. After that I had nothing. I had no clothes, I had no anything.” Sharon’s sister Betty Katzenelson added, “And no source of income because their source of income was burned.” [22] However, their store may have been one of the targeted businesses emphasized by Knott and Lawrence. Both cited corner stores that exploitatively cashed checks for people in the community as leading to retribution violence. Sharon and Betty recalled that their store was a place where community members lined up outside the door on welfare check day to cash their checks. Sharon said, “[T]hey had a trust in my parents, in fact so much so that my parents had a little file box, and in the file box were just file cards with people’s names on them, and if they didn’t have the money to buy their toiletries or to get whatever they needed, my parents would write their names down” for later payment. She added, “No interest or anything like that, it was just a very trusting kind of system.” [23] It is possible that Sharon and Betty’s parents may have not been fully honest with them about there being no interest, in which case they could fall into the targeted category emphasized by Knott and Lawrence.

The burning and looting of the Lewis furniture store does not appear targeted. It seems to be an example of indiscriminate destruction caused by the spring 1968 unrest. Store owner Ted Lewis recalled that a community member warned him as the unrest neared, telling him, “You better get out [be]cause they’re going to come and burn up the place.” He claimed that he immediately gathered the family and “just got in the car and left.” Then, the building was burnt “down to the ground.” [24] He remained at home with his family in their predominantly white neighborhood until the unrest died down, then returned to the annihilated store. When the interviewer asked, “And how long would you say it took for you to rebuild to the point that you were at before the riots, in terms of you[r] assets?” Lewis responded, “Never, never came back. Never came back to where it was.” [25] This example shows that in some cases the unrest did harm people indiscriminately. While Ted Lewis held some conservative views on the impacts of the unrest, he did not express any explicitly negative views on the Black community. But social views did not stop the destruction of his business.

In Baltimore City, the spring of 1968 brought deep sadness, anger, community-building, targeted violence, and indiscriminate destruction. Amidst these occasionally conflicting impacts, Black Baltimoreans persisted in asserting their identities and interests. Contrary to popular recollections that the unrest was indiscriminate, these interviews show that in some cases violence was targeted. Businesses that harmed Black Baltimorean communities were more likely to be burned and looted. There were also cases where violence was untargeted. Black Baltimoreans emerged from spring 1968 traumatized but also increasingly militant and cohesive. For some white Baltimoreans, the unrest led to a rethinking of how they could contribute to the betterment of Baltimore race relations. For others, their thinking continued to embody systemic racism rather than consider the underlying causes of Black community suffering. These interviews make clear that experiences of “Baltimore ‘68” were highly variant. No experience or recollection is more or less valid than another. However, this article amplifies Black experiences to combat historical erasure driven by systemic racism.

This series will be continued with “Part Four” on Saturday, June 10, as our regularly scheduled weekly feature.

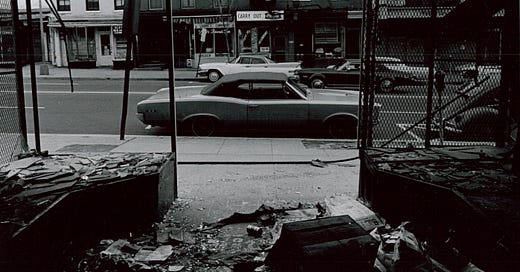

[1] “Photograph of 1138 Street Baltimore City, 1969 After the Riots,” photograph, 1969, National Archives, unrestricted access, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/178690545.

[2] Nia Redmon, Baltimore '68: Riots & Rebirth Collection (hereafter BSR), University of Baltimore, May 12, 2007, 2, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/redmon.pdf.

[3] Dorothy Hurst, BSR, University of Baltimore, Fall 2007, 2, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/hurst.pdf.

[4] Frieda Halderon, BSR, University of Baltimore, December 3, 2006, 4, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/halderon.pdf.

[5] Yvonne Hardy-Phillips, BSR, University of Baltimore, January 7, 2008, 33, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/hardy_phillips.pdf.

[6] Francis J. Knott, BSR, University of Baltimore, February 27, 2008, 6, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/knott.pdf.

[7] Richard Lawrence, BSR, University of Baltimore, unspecified date, 13, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/Lawrence.pdf.

[8] Knott, BSR, February 27, 2008, 6.

[9] Lawrence, BSR, University of Baltimore, unspecified date, 14.

[10] Herbert Hardrick, BSR, University of Baltimore, March 15, 2007, 2-4, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/Hardrick.pdf.

[11] Hardrick, BSR, University of Baltimore, March 15, 2007, 10.

[12] Hardrick, BSR, University of Baltimore, March 15, 2007, 13-14.

[13] Hardrick, BSR, University of Baltimore, March 15, 2007, 16.

[14] Harold L. Knight, BSR, University of Baltimore, January 15, 2008, 1, 4, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/knight%20rev.pdf.

[15] Knight, BSR, University of Baltimore, January 15, 2008, 13.

[16] Lillie Hyman, BSR, University of Baltimore, March 21, 2007, 13, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/hyman.pdf.

[17] See Hyman, BSR, March 21, 2007, 13; Knight, BSR, January 15, 2008, 10.

[18] Annie Perkins, BSR, University of Baltimore, unspecified date, 5, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/perkins.pdf.

[19] Perkins, BSR, unspecified date, 6.

[20] Ted & Jane Lewis, BSR, University of Baltimore, unspecified date, 10, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/lewis.pdf.

[21] Pats Family, BSR, University of Baltimore, February 20, 2007, 1-2, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/pats.pdf.

[22] Pats Family, BSR, February 20, 2007, 8.

[23] Pats Family, BSR, February 20, 2007, 4.

[24] Lewis, BSR, University of Baltimore, unspecified date, 3.

[25] Lewis, BSR, University of Baltimore, unspecified date, 9.