In 2008, the University of Baltimore held a series of events for the “Baltimore ‘68: Riots and Rebirth” project. This was to commemorate the fortieth anniversary of the unrest that erupted in Baltimore following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. At the time of writing, in 2023, fifteen years have passed since this commemoration. This seems enough time for a re-examination of the project, considering it within past and present contexts. This investigation will delve specifically into the project’s oral history interviews, to place at the center of analysis the voices of people involved in the events of 1968. All interviews are dated between 2006 and 2008. Project developers organized the oral histories alphabetically into four pages, with an average of about seventeen interviews per page. Each part of this series will examine one page of interviews, working from first to last to reflect how the content is presented to site visitors. After reviewing the first group of interviews, it is clear Baltimore’s extreme system of residential segregation had the greatest direct impact on individual experiences of the unrest. This unrest was concentrated in neighborhoods that were almost entirely Black. Relatedly, interactions with law enforcement and military forces were intense and frequent in Black neighborhoods. White areas reported little impact. All around Baltimore, 1968 fostered a combination of despair and hope about the racial future of the city and the country. This complex emotional experience was significantly influenced by race and thus by neighborhood. The Baltimorean experience of 1968 was highly segregated, just like life in the city itself. These experiences did however create some optimism for the future of integration in Baltimore under the federal civil rights legislation of the mid-1960s.

The term unrest is used here to refer to the actions of people who expressed dissatisfaction with recent events by demonstrating in the streets of Baltimore City. Unrest is a favorable term since it is the opposite of rest, meaning to act in support of one’s beliefs. Baltimoreans took action. The interviews themselves contain interesting discussion of this terminology. In 1968, interviewee Art Cohen was a thirty-year-old white legal aid attorney who moved to Baltimore from Washington, D.C. in the fall of 1967. Early in the interview, when the interviewer used the word “riot” for the first time, Cohen quickly objected to the term. He said, “I don’t use the word riot because I don’t see it that way.” He added, “Riot is a negative word and that’s the reason I don’t use it. I felt at that point people had so much grief and sense of loss and anger that they had to express it somehow.” [1] In another interview, a black man named Rev. Marion Bascom made clear to the interviewer that he “would rather call that experience … disturbances rather than riots.” He explained, “I call it disturbances, because in a real sense, there was, during that time, so much hope.” [2] The role of hope in all of this will be expanded on soon, but first there is more to be said about terminology.

Interviewees Cohen and Rev. Bascom both expressed specific preference for the word “disturbance.” Cohen said, “The word that the Kerner Commission uses is civil disorder or civil disturbance,” and then went on to use the latter term extensively. [3] The Kerner Commission was also known as the National Advisory Committee on Civil Disorders and was created by President Johnson. As historian Elizabeth Hinton writes, “In its final report of February 1968 (which went on to become a national bestseller as a mass-market paperback), the commission warned … that absent a massive investment into poor Black communities, rebellion and ‘white retaliation’ would entrench racial inequality as a permanent feature of American life.” The popularity of the report, noted by Hinton, is validated by Cohen referring to it as inspiring his word choice for the events. As Hinton emphasizes, the calls of the Kerner Commission went largely unaddressed on the federal level. [4] Unfortunately, it appears its terminology choices had greater impact than its policy recommendations.

The “Baltimore ‘68” interviews shed light on the landscape of residential segregation in 1960s Baltimore. Of the eighteen interviews in the first group, four of them are with individuals identified as Black. The first of these we already engaged with, the discussion with Rev. Bascom and his wife Dorothy Bascom. Another of the Black interviewees is Robert Birt. In 1968, he was a teenager living in East Baltimore’s Latrobe public housing project. He recalls that most students at his school at the time were white, “But the African American part of the student population was growing.” This reflects the implementation of the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision mandating school integration. However, Birt’s residential experience remained segregated. As he recalls, “Prior to high school, my frame of reference was the neighborhood and, of course, it was a black neighborhood. There just weren’t that many white people around.” [5] Interviewee Juanita Crider provides a similar perspective. Her view on residential segregation is illuminative of what the experience was like on a fundamental level as she was seven years old at the time. Reflecting on “the racial mood” at the time, she stated, “I would say it was pretty isolated, us and them kinda thing, not, when I say us and them, not an animosity feeling, its [sic] just like you know, the White people are here and here and we lived in a, you know they had their neighborhoods, we had our neighborhoods.” [6] It is insightful to reflect on Birt and Crider’s recollections of segregation in 1960s Baltimore because being young at the time their lived experiences were not yet imbued with extensive political and civic understandings.

Birt also discusses how the events of 1968 changed residential segregation in Baltimore. He recalls. “It was after ’68 – well, who knows when it really started – that a sizable white flight got to be noticeable. I think it was after ’68 that the city became predominantly black.” [7] This suggests an intriguing connection between the events of 1968 and accelerated white flight out of Baltimore City. Taken further, perhaps the social change that accompanied mid-1960s civil rights legislation provided added motivation for white Baltimoreans to move out of the city. One interviewee, a white Jewish drycleaner named Frank Bressler, drew this connection explicitly. The interviewer asked, “how Baltimore changed after the riots and how your neighborhood changed.” Bressler responded, “Well what happened is it caused a flight of people from the areas, people who used to live out in, Forest Park area used to be predominantly Jewish and gradually as the neighborhood changed they moved out … [then] they moved further out into the valley and further, further away.” He added, “Going back to prior to WWII there was a ring around Baltimore … which says no one can sell to blacks beyond North Ave.” [8] It is interesting to consider how the broader civil rights movement and changes within Baltimore City itself contributed to these demographic shifts in addition to the unrest following the assassination of Dr. King.

Frank Bressler also made the important point that Baltimore white flight started long before 1968. This is reflected in the experiences of interviewees who already lived outside the city during the events of 1968. Interviewee Tom Brown, a white man who was a Montgomery County high school student at the time, embodies this. The general theme of his interview is reflected in his statement, “Just a suburban white kid, clueless, [laughter] that’s kind of what it was.” [9] He claimed near-complete isolation from and lack of understanding of the unrest or the Civil Rights Movement. Interviewee Donna Baust, a white woman who at the time was an 8-year-old living in Baltimore County, adds to this sense of white isolation. The interviewer asked her, “before the riots, which were in 1968, what kind of interactions did you have with people of other races?” Baust answered, “Absolutely none.” She added, “They lived in the city, they lived in Baltimore city.” [10] The situation is put simply here by someone who was eight at the time, white people lived in Baltimore County and Black people lived in Baltimore City. As Birt and Bressler mention, this seems to get more drastic after 1968. [11] Census data confirms this. In the 1960 census, Baltimore City had 939,024 white residents and 610,608 Black residents. [12] In the 1980 census, the city had 345,113 white residents, officially a minority of the population. It had 431,151 Black residents. [13] Most recently, the 2020 census reported Baltimore City’s population to be 61.6% Black and 29.2% white. [14] In 1968, extreme racial segregation also greatly impacted how Baltimoreans interacted with law enforcement and the military.

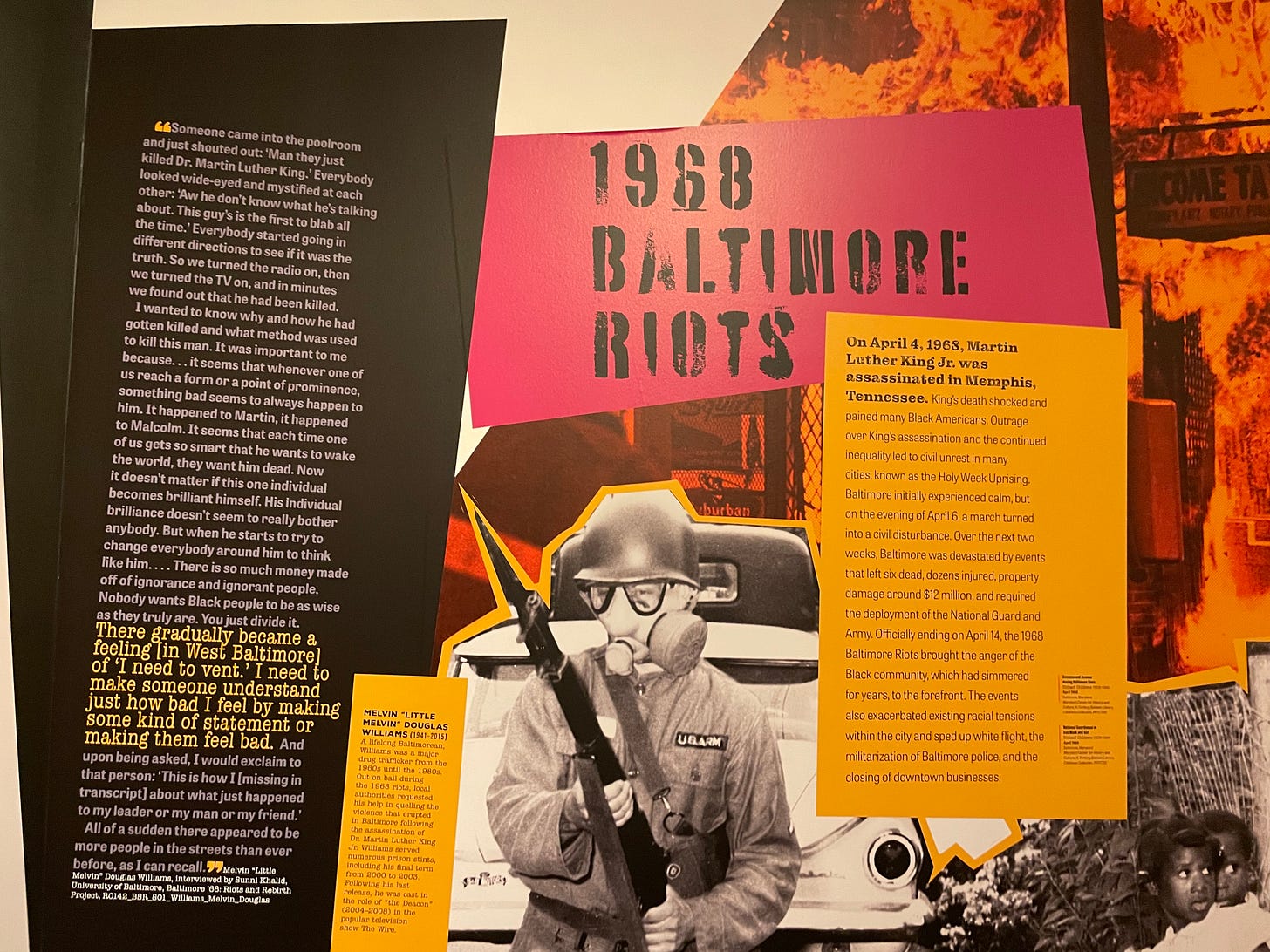

Once the Baltimore unrest started, Maryland Governor Spiro Agnew called in the National Guard and the Baltimore Police Department unleashed a heavy presence around the city. [15] President Johnson added additional muscle by calling in regular Army troops. [16] Both the police and the military concentrated themselves in the city’s Black neighborhoods. Interviewee Theodore Cornblatt, a white man who was a 25-year-old attorney in 1968, discusses his experience living in a predominantly white neighborhood. The interviewer asked, “And you said there was no National Guard, business as usual?” Cornblatt put it bluntly, his neighborhood saw “No effect.” [17] Some white Baltimoreans, such as interviewees Hunter and Barbara Alfriend, lived in the inner city and thus were directly exposed to the National Guard and military presence. The Alfriends recalled watching the unrest from their roof and noted that while in the city, their neighborhood was “99 percent white.” [18] Being white and living in such a neighborhood, it appears they were of little concern to the occupying forces.

In his interview, Robert Birt sheds light on what the National Guard and army occupation of the city was like for Black Baltimoreans. The term occupation is used here because this is the term Birt uses to describe how it felt to him. Recalling what this experience was like as a Black teenager, he said, “I didn’t have all the words I might use for it now, but on a certain emotional level, I just saw them as an occupation. They were here to defend white property and to enforce white law.” [19] These perceived racialized goals of the occupiers show how their presence impacted Black and white Baltimoreans differently. Birt also addresses how Black Baltimoreans experienced the police in that period, noting, “They were known to be quite abusive.” He added, “and the police – I guess the police force in those days was maybe eighty to ninety percent white – [and] many of them had an in your face attitude.” [20] The presence of the National Guard, army, and police in 1968 Baltimore City impacted residents in different ways according to race.

The emotional interplay of hope and despair in Baltimore in 1968 also directly correlated with race and neighborhood. There was some hope amongst the city’s Black community that the federal civil rights legislation of the mid-1960s and signs of social change meant things were changing for the better. Interviewee Jewell Chambers, a Black woman who in 1968 was a 25-year-old reporter for the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper, reflects on this. Regarding the “racial mood” in the city prior to the unrest, she said, “Tense is not the word I use. I think a better thing was the idea … that things are changing, times they are a changing. It’s a cliché but I think that’s where it is; that if we keep on going we are changing the status [of race relations].” [21] While tensions still existed, for Chambers hope shone through. But such optimism was rattled by the Dr. King assassination. Interviewee William Costello, who in 1968 was a 34-year-old journalist and businessman living in Towson, observed this mix of emotions from a white perspective. He stated, “because of Dr. King, and probably Malcolm X, there was hope, tremendous hope among the black population, that things were going to be getting better for them. Because they could see some change and I mean we could all see some change.” [22] He added some insights into impacts of 1968 on Baltimore’s white population, noting, “I think that the white population of Baltimore… I think those who were sleeping through, you know the era, I think that it woke them up and alerted them to the fact that the African-American community wanted its rightful place in America as citizens.” He added that this, “probably helped integration.” [23] Taking these perspectives together, it seems the events of 1968 in Baltimore City produced a powerful combination of grief, hope, and reckoning.

In 1968, the unrest in Baltimore City following the assassination of Dr. King affected Baltimoreans differently according to race. Since the city was extremely racially segregated, this quite literally meant different interactions with law enforcement, the military, and civil disturbance. For some white Baltimoreans, the unrest took place completely outside of their lived experience. It had little impact on their daily life. For many Black Baltimoreans living in the city, the unrest and the state response to it was all-encompassing. Authorities militarized or policed nearly every streetcorner in Black neighborhoods, and Black Baltimoreans faced heavy scrutiny. Many were arrested, for offenses as simple as violating aggressive curfews imposed by Governor Agnew. There was however still some hope in the air for the future of race relations in the city and country. Civil rights breakthroughs at the federal level had clear momentum in the latter-half of the 1960s, and Baltimoreans started to perceive significant social change on race relations. From the “Baltimore ‘68” interviews featured here, the general Black Baltimorean response was that the events of 1968 showed how much racism remained in the city and how much work remained to be done. For some white residents, it seems the Black Baltimorean reaction to Dr. King’s assassination and the unrest that followed provided a wake-up call. While this may have helped integration in later years, much work remains to be done on racial inequality and race relations in Baltimore City today.

This series will be continued with “Part Two” on Saturday, May 27, as our regularly scheduled weekly feature.

[1] Art Cohen, Baltimore '68: Riots & Rebirth Collection (hereafter BSR), University of Baltimore, July 2007 [final, corrected version: March 14, 2008], 5-6, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/cohen.pdf.

[2] Marion and Dorothy Bascom, BSR, University of Baltimore, November 4, 2006, 10, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/bascom.pdf.

[3] Cohen, BSR, July 2007, 5.

[4] Elizabeth Hinton, America on Fire: The Untold Story of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s (New York: Liveright, 2021), 9.

[5] Robert Birt, BSR, University of Baltimore, July 7, 2007, 1, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/birt.pdf.

[6] Juanita Crider, BSR, University of Baltimore, unspecified date, 4, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/crider.pdf.

[7] Birt, BSR, July 7, 2007, 8.

[8] Frank Bressler, BSR, University of Baltimore, unspecified date, 13, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/bressler.pdf.

[9] Tom Brown, BSR, University of Baltimore, unspecified date, 11, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/brown.pdf.

[10] Donna Baust, BSR, University of Baltimore, November 12, 2007, 2, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/oral-histories1.html.

[11] Birt, BSR, July 7, 2007, 8; Bressler, BSR, unspecified date, 13.

[12] U.S. Bureau of the Census, U.S. Censuses of Population and Housing: 1960, Census Tracts, Final Report PHC(1)-13, Baltimore, Md., 15, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1960/population-and-housing-phc-1/41953654v1ch5.pdf.

[13] U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics (1990 CP-1) and 1990 Census of Housing, General Housing Characteristics (1990 CH-1), report series published 1992-1993, 1, https://planning.maryland.gov/MSDC/Documents/Census/historical_census/sf1_80-00/baci80-00.pdf.

[14] U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2020 Census of Population, “QuickFacts: Baltimore City, Maryland,” https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/baltimorecitymaryland/RHI125221#RHI125221.

[15] Alex Csicsek, “Spiro T. Agnew and the Burning of Baltimore,” in Baltimore ’68: Riots and Rebirth in an American City, eds. Jessica J. Elfenbein, Thomas L. Hollowak, and Elizabeth M. Nix (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2011), 72, Kindle edition.

[16] Peter B. Levy, “The Dream Deferred: The Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Holy Week Uprisings of 1968,” in Baltimore ’68: Riots and Rebirth in an American City, eds. Jessica J. Elfenbein, Thomas L. Hollowak, and Elizabeth M. Nix (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2011), 6, Kindle edition.

[17] Theodore Cornblatt, Baltimore '68: Riots & Rebirth Collection (hereafter BSR), University of Baltimore, December 20, 2007, 9, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/cornblatt.pdf.

[18] Hunter and Barbara Alfriend, BSR, University of Baltimore, December 8, 2006, 4, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/alfriend.pdf.

[19] Birt, BSR, July 7, 2007, 5.

[20] Birt, BSR, July 7, 2007, 4.

[21] Jewell Chambers, BSR, University of Baltimore, February 7, 2008, 5, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/ChambersTranscript.pdf.

[22] William Costello, BSR, University of Baltimore, May 7, 2008, 8, http://archives.ubalt.edu/bsr/oral-histories/transcripts/costello.pdf.

[23] Costello, BSR, May 7, 2008, 11.