How Sergeant Major Christian A. Fleetwood Spent His 24th Birthday While in the Union Army

BHW 45: December 9, 2023

Black Baltimorean Sergeant Major Christian Abraham Fleetwood celebrated his twenty-fourth birthday on Thursday, July 21, 1864, while serving in the Union Army. His diary entry for this day provides a window into the lived experiences of a Black Baltimorean who directly participated in the U.S. Civil War. He writes that he received a letter from a doctor, likely an itinerant physician for the army. Then he acknowledges it is his birthday, before describing he and his colleagues being chased by Confederate troops. After escaping this pursuit with his life, he settles down to read a novel titled The Trials of the Soldier’s Wife, before patrolling the area where his regiment rested. They then ate supper and followed their meal with some singing. But the singing stopped when Confederate gunfire was heard in the distance. Fleetwood watched and listened to the shelling before heading to bed. As he retired for the evening, he made a point of remarking that the day’s weather was “fine” and that the “Night [was] beautiful.” [2] The next two days he recorded in his diary that he ran into some Baltimoreans, an occurrence he did not mention happening over the previous fifty-five days. [3] Perhaps this connection to home was a welcome late birthday present. His twenty-fourth birthday was one of many days that Fleetwood spent in the 4th United States Colored Infantry (USCI) regiment of the Union Army from 1864 to 1866. Its details provide insights into a Black Baltimorean frontline Civil War experience. [4] By delving into and contextualizing his birthday diary entry, we learn what he saw as sufficiently important to write down. Emphasizing and expanding upon what Fleetwood decided to record works towards preserving what he considered memorable in historical memory.

The first line of Fleetwood’s July 1864 birthday diary entry acknowledges receiving a “Letter from Dr.,” presumably a physician. It is unclear what sort of news he received. As historian Margaret Humphreys emphasizes, “Even by the standard of the time, African American regiments received decidedly second-class medical care . . . Although it is difficult to quantify the impact of inadequate medical care on the high rates of disease and death among black regiments, the evidence indicates that poor care was an important factor in these outcomes.” [5] The medical team for Fleetwood’s 4th USCI regiment was led by Surgeon John W. Mitchell along with Assistant Surgeons George G. Odiorne and Kenneth Wharry. [6] However, in the summer of 1864, around the time of Fleetwood’s birthday, Wharry left the regiment to return to his private medical practice. Historian Edward G. Longacre points out that “Wharry’s departure was ill timed, for the regiment’s medical staff was already overtaxed.” [7] It thus appears likely that when Fleetwood received correspondence from a doctor on his birthday, the medical care addressed in the letter was delayed or minimal.

Flawed and understaffed medical care negatively impacted both the morale and the physical performance of USCI regiments. In some cases, medical malpractice led to the enlistment of African Americans who should have been exempt. For example, Black Marylander William Jackson provided two letters from physicians attesting that he could not serve in the conflict because he suffered from epilepsy. Recruiting officers rejected the physician letters, brought in an army surgeon who deemed him fit to serve, and rushed Jackson onto the battlefield. [8] There is no evidence of Fleetwood suffering from any medical conditions, so it seems he was able to avoid the most damaging consequences of mediocre care for Black troops.

Around his twenty-fourth birthday, Fleetwood’s regiment was camped near the city of New Bern, North Carolina. [9] Earlier that month, he spent three or four days serving in “the battery,” which involved securing ammunition and maintaining artillery fire for extended periods. By his birthday, he returned to a routine of going back and forth between the camp near New Bern and various assigned patrol or occupation locations. For example, on July 17 he wrote that he and some colleagues were “Ordered out & re-occupied our old Caves & Dens.” [10] When he describes being “Chased by inf[antry] and cav[alry]” along with his colleagues “Chap[lain] and Han[dy]” on his birthday, it is likely this happened while they were patrolling and reporting on sites occupied or otherwise deemed important. [11] By the end of July, he was back in the battery. [12]

It is remarkable that on Fleetwood’s birthday he read a Confederate novel, given that he was serving in the Union Army and battling Confederate combatants on a regular basis. As author Alex St. Clair Abrams explains in this particular novel’s preface: “The plot of this little work was first thought of by the writer in the month of December, 1862, on hearing the story of a soldier from New Orleans, who arrived from Camp Douglas just in time to see his wife die at Jackson, Mississippi.” [13] The book is explicitly pro-Confederate in its subject matter and presentation. For example, the author writes, “Kind reader, have you ever been to New Orleans? If not, we will attempt to describe the metropolis of the Confederate States of America . . . It was in the month of May, 1861, that our story commences. Secession had been resorted to as the last chance left the South for the preservation of her rights.” [14] Perhaps reading this description of how the South was fighting for the right to preserve the institution of slavery provided Fleetwood with further motivation to battle against the Confederate cause. Relatedly, the book also describes the purchase of an enslaved person at a domestic slave trade site. [15] It is likely that these portrayals of race-based slavery evoked significant emotion in Fleetwood. However, he may have not taken the book overly seriously, instead viewing it as an escape from the perils of camp life.

Fleetwood’s description of the “singing” and “Concert” after supper is as close as this birthday diary entry gets to a clear expression of joy. [16] Singing and music played significant roles in his life and it is heartwarming that he was able to continue these activities to some extent while enlisted. Before the war, he sang in a choir in Baltimore and enjoyed attending concerts in the city. [17] After the war, he moved to Washington, D.C. and became a choral director for several churches. He also joined an amateur theater company and acted in plays to supplement his other arts activities. [18] It is unfortunate that his post-supper singing time was cut short by Confederate gunfire, but surely quieting down was a wise response to avoid attracting further enemy attention.

While Fleetwood’s diary entries return to his regular routines of patrolling, occupying, and shooting after his birthday, the two immediately following days provided a welcome taste of home. The day after his birthday, July 22, he describes running into several Baltimoreans. Then the next day he wrote, “Found more Baltimoreans still.” Given that he spent the fifty-five days immediately preceding his birthday without noting encountering any Baltimoreans, this late birthday present is notable. That is of course assuming that he was happy to see them, which may have not been the case. No further details are provided other than these people also being from Baltimore. Since they were conversing, they surely were on the Union side. Baltimore had numerous Confederate sympathizers but most Baltimoreans supported the Union cause. The city’s secessionist and Confederate sympathies peaked near the start of the war, as evidenced by the pro-secession April 1861 Pratt Street Riot. Yet, by the end of 1861, Baltimore City was undoubtedly Unionist. [19]

Christian Abraham Fleetwood’s twenty-fourth birthday provides a window into Black Baltimorean experiences of serving in the Union Army during the American Civil War. His story illuminates the inequities of medical care provided to African American soldiers, demonstrates the routines of camp life, and shows how some soldiers spent their free time. He ran into some Baltimoreans over the course of these activities and found these occurrences notable, showing his continued thinking about home throughout his service. Shortly after the war, Fleetwood moved from Baltimore, where he was born and raised, to Washington, D.C. It was here in the nation’s capital that he sought to secure further military leadership positions. However, he ran into harsh systemic racism and segregation. Despite winning the Congressional Medal of Honor for his efforts to preserve his regiment’s flags at the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm in September 1864, racism blocked his advancement. [20] Shortly after this battle, every commissioned officer in his regiment, who by requirement for such positions were all white, recommended his promotion to commissioned officer. This request was rejected because he was Black. [21] When Washington, D.C. created its National Guard in 1887, he was appointed as a major. But the Guard’s commander took issue with Black battalions and tried to disband them. Fleetwood resigned in protest. [22] Perhaps in the days that followed he glanced at his Medal of Honor and wondered what else he could have possibly done for his country to merit a military leadership promotion.

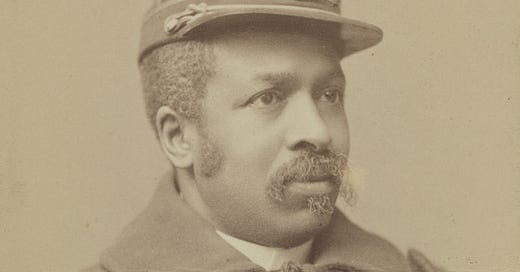

[1] Merritt & VanWagner, “Christian Abraham Fleetwood,” albumen silver print (Washington, D.C., c. 1890), National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian open access, https://www.si.edu/object/christian-abraham-fleetwood:npg_NPG.2015.92.

[2] Sgt. Major Christian A. Fleetwood, “Diary of Sgt. Major Christian A. Fleetwood, 4th U.S. Colored Troops, excerpts, 1864,” July 21, 1864, National Humanities Center, 3, http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/maai/identity/text7/fleetwooddiary.pdf.

[3] See Sgt. Major Christian A. Fleetwood, Diary of Christian A. Fleetwood for 1864, July 22, 1864, Christian A. Fleetwood Papers, Library of Congress (Washington, D.C.), 119, https://www.loc.gov/item/mss20784_01/; Sgt. Major Christian A. Fleetwood, Diary of Christian A. Fleetwood for 1864, July 23, 1864, Christian A. Fleetwood Papers, Library of Congress (Washington, D.C.), 120, https://www.loc.gov/item/mss20784_01/.

[4] Charles Johnson, “Fleetwood Biography,” National Parks Service, February 26, 2015, https://www.nps.gov/rich/learn/historyculture/cfbio.htm.

[5] Margaret Humphreys, Intensely Human: The Health of the Black Soldier in the American Civil War (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 57, https://archive.org/details/intenselyhumanhe0000hump.

[6] Edward G. Longacre, A Regiment of Slaves: The 4th United States Colored Infantry, 1863-1866 (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2003), 19, https://archive.org/details/regimentofslaves0000long.

[7] Longacre, A Regiment of Slaves, 169.

[8] Timothy J. Orr, “‘The Fighting Sons of ‘My Maryland’’: The Recruitment of Union Regiments in Baltimore, 1861-1865, in The Civil War in Maryland Reconsidered, eds. Charles W. Mitchell and Jean H. Baker (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2021), 247, Kindle edition.

[9] Longacre, A Regiment of Slaves, 166.

[10] Sgt. Major Christian A. Fleetwood, Diary of Christian A. Fleetwood for 1864, July 17, 1864, Christian A. Fleetwood Papers, Library of Congress (Washington, D.C.), 117, https://www.loc.gov/item/mss20784_01/.

[11] Fleetwood, “Diary of Sgt. Major Christian A. Fleetwood, Excerpts,” 4.

[12] Sgt. Major Christian A. Fleetwood, Diary of Christian A. Fleetwood for 1864, July 31, 1864, Christian A. Fleetwood Papers, Library of Congress (Washington, D.C.), 124, https://www.loc.gov/item/mss20784_01/.

[13] Alex St. Clair Abrams, The Trials of the Soldier’s Wife: A Tale of the Second American Revolution (Atlanta, GA: Intelligencer Steam Power Presses, 1864), 5-6, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/17955/17955-h/17955-h.htm.

[14] Abrams, The Trials of the Soldier’s Wife, 7.

[15] Abrams, The Trials of the Soldier’s Wife, 54.

[16] Fleetwood, “Diary of Sgt. Major Christian A. Fleetwood, Excerpts,” 4.

[17] Elizabeth D. Leonard, Men of Color to Arms!: Black Soldiers, Indian Wars, and the Quest for Equality (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2010), 3-4, https://archive.org/details/menofcolortoarms0000leon.

[18] Roger D. Cunningham, “‘His Influence with the Colored People is Marked’: Christian Fleetwood’s Quest for Command in the War with Spain and Its Aftermath,” Army History 51 (Winter 2001): 21, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26304923.

[19] Orr, “The Fighting Sons of ‘My Maryland,” 228.

[20] U.S. Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, Medal of Honor Recipients, 1863-1978 (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1979), 88, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/pur1.32754060295262.

[21] Leonard, Men of Color to Arms!, 14.

[22] Cunningham, “His Influence with the Colored People,” 21.