Henrietta Lacks, Johns Hopkins Hospital, and Baltimore Racial Histories of Medicine

BHW 23: July 8, 2023

CONTENT WARNING: reproductive violence and intergenerational medical malpractice trauma

In 1951, researchers at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore took cell samples from the cervix of Black Baltimorean cervical cancer patient Henrietta Lacks without her consent. These cells became “the first immortal human cell line,” called “HeLa,” one of the most impactful scientific breakthroughs in American history. [2] There are plenty of publications from medical and scientific journals analyzing the case of Henrietta Lacks. The most prominent book on the subject is The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (2010) by Rebecca Skloot, a science journalist, and will be the subject of close analysis here. It is important to apply a historical lens to this story and to view it through its location at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. During a 2018 event at Stanford University, one of Lacks’s descendants said, “Everything we know about our grandmother came from the book [by Skloot].” [3] This is potentially problematic given the book only represents one author’s take on this person’s life. By adding historical analysis into established narratives, with an emphasis on the story’s Baltimore location, we will shed new light on this history. We focus on the historical trends leading Henrietta to move to Baltimore, her relationship with Johns Hopkins Hospital, and histories of medical abuse of African Americans.

Henrietta Lacks grew up in the very rural Clover, Virginia, before moving to Baltimore with her husband and children in the 1940s as part of the Great Migration. In Clover, her and her family worked the same tobacco fields as their enslaved ancestors. [4] Around mid-century, Baltimore’s Sparrows Point developed into a steel production hub. It drew a mass migration of workers. Henrietta’s family relocated specifically to Turner Station, an African American neighborhood directly adjacent to the Sparrows Point company town. [5] The company, initially Maryland Steel before it was purchased by Bethlehem Steel in 1916, made a point of recruiting African American men. [6] However, both companies discriminated heavily against Black laborers in both pay and job selection during this era of intense racial segregation in Baltimore. [7] Despite this, the rising Black working class had significant economic success in this community relative to other Black people around the United States in this period. [8] As historian Blair L.M. Kelley writes in her work on the Black working class, “Black folks’ sense of self was supported not by the jobs they held but by their place in their own communities… Within such havens, Black people created the collective power that would drive their political engagement with the world.” [9] Turner Station was one of these havens of Black empowerment in the mid-twentieth century, and this is where Henrietta Lacks lived when she learned that she had cervical cancer.

In January 1951, Henrietta went to her doctor, who quickly referred her to the Johns Hopkins Hospital gynecology clinic. [10] On February 5, Johns Hopkins Hospital called her with news that her cancerous tumor was malignant. The next day, she went to the clinic and began surgical treatment. That day, the surgeon removed tissue samples from both her tumor and the healthy portion of her cervix without asking for consent. [11] In Skloot’s book, this is where the story departs from its focus on Henrietta herself, shifting to medical analysis reflective of the author’s scientific background. Henrietta died in Johns Hopkins Hospital on October 4, 1951, eight months after beginning treatment. Skloot follows the death event with many chapters of scientific analysis, with occasional interjections to check in on Henrietta’s family. [12] Let us keep the analytical needle on Henrietta herself, eschewing the properties of her cells to focus on her life experiences in Baltimore.

As some critics suggest, one of the most striking omissions from Skloot’s work is the lack of focused analysis on Henrietta’s institutionalized daughter Elsie. [13] Henrietta’s relationship to Elsie extends her relationship to the allegedly medical strong-arm of the state. It also provides a glimpse into some of this story’s most emotional human experiences. Elsie was forcibly placed into the former Hospital for the Negro Insane, then re-named Crownsville State Hospital. After diagnosing Elsie with epilepsy, her doctors deemed her in need of institutionalization and sent her to this hospital about a ninety-minute drive from Baltimore. [14] Absent from Skloot’s description of these events is that such institutionalization of Black children historically resulted from white doctors’ racist paternalistic views of Black parental abilities. As disability studies scholars Nirmala Erevelles and Michael Gill point out in their critique of Skloot’s book, Elsie’s “incarceration is predicated on a[n] ableist, capitalist, white supremacist solution to the ‘problem of disability.’” [15] While missing these historical themes, Skloot does provide some of her most compassionate analysis in examining Henrietta’s late relationship with her daughter. She recalls her conversation with Henrietta’s cousin Emmett, who took her to visit Elsie in what would become the last time anyone visited Elsie. Skloot writes, “Henrietta wrapped her arms around Elsie, looked her long and hard in the eyes, then turned to Emmett. ‘She look like she doin better,’ Henrietta said. ‘Yeah, Elsie look nice and clean and everything.’ They sat in silence for a long time. Henrietta seemed relieved, almost desperate to see Elsie looking okay.” [16] This desperation for good news evokes the pain Henrietta experienced as her health deteriorated in this the last year of her life.

Just like Henrietta, Elsie underwent non-consensual medical experimentation during her hospitalization. Both were taken from Baltimore to the nearest specialized state medical facility for treatment, Henrietta to Johns Hopkins Hospital and Elsie to Crownsville State Hospital. For Henrietta, the medical experimentation likely had no direct correlation with her death. There is no rational argument that the taking of cell samples impacted the fatal progression of her cancer. For Elsie, the causal relationship is less clear. Elsie suffered from epilepsy and this was the diagnosis that landed her at Crownsville. As Skloot notes, scientists at Crownsville often conducted non-consensual research on patients. This included a “study titled ‘Pneumoencephalographic and skull x-ray studies in 100 epileptics.’” Skloot explains, “Pneumoencephalography involved drilling holes into the skulls of research subjects, draining the fluid from their brains, and pumping air or helium into the skull in place of the fluid to allow crisp X-rays of the brain through the skull.” This practice was halted in the 1970s because it caused permanent brain damage and paralysis. Elsie died at Crownsville in 1955. [17] Henrietta and Elsie’s stories are continuations of a long history of medical racism in the United States.

Henrietta was treated by the gynecology department at Johns Hopkins Hospital because her cancer started in her cervix. American gynecology’s history is indelibly connected with research conducted on enslaved Black women by the doctors and institutions who enslaved them. Adding an additional layer, many of the nurses who worked in these nineteenth-century institutions were also enslaved Black women. [18] That Skloot does not look back in time to reflect on this history is likely reflective of her not considering herself a historian. As historian Deirdre Cooper Owens argues, the “Father of American Gynecology” Dr. James Marion Sims enslaved his medical staff, forcing them to experiment on enslaved women in the mid-nineteenth century. [19] The labor of and non-consensual experimentation on enslaved women provided the groundwork for the gynecological profession that exploited Henrietta. Owens asserts that the Black women who labored as nurses under Sims should be considered the “mothers” of gynecology to go along with Sims’s paternalistic title.

The history of gynecology shows that medical racism and its connections to slavery go far beyond the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, the most well-known example of this. For context, this Tuskegee study involved government-led denial of treatment for syphilis to 399 African American men. This was done for experimental purposes, leading to many deaths. As medical humanities scholar Vanessa Northington Gamble writes, “The Tuskegee Syphilis Study is frequently described as the singular reason behind African American distrust of the institutions of medicine and public health. Such an interpretation neglects a crucial historical point: the mistrust predated public revelations about the Tuskegee study.” [20] This history is reflected in the response that Skloot recalls receiving when she talked to a gynecology professor at the HBCU Morehouse College about the Lacks case. Dr. Roland Pattillo asked her, “What do you know about African Americans and science?” She recalls responding by telling him about the Tuskegee study, “like I was giving an oral report in history class.” Pattillo’s next question was, “What else?” [21] Non-consensual scientific experimentation on African American people is foundational to the histories of American science and medicine.

These histories of racial exploitation also connect directly to the story of Johns Hopkins himself, the creator of the hospital that non-consensually removed Henrietta’s cells. Hopkins came from a family of enslavers and was himself an enslaver. Skloot emphasizes that when he decided to create the Johns Hopkins Hospital, he wanted it to treat people regardless of race. She presents this as a sort of saving grace for the man’s legacy. [22] Any argument for redeeming his legacy with such a hospital must consider that Hopkins died nine months after sending his first letter to the hospital trustees about the principles he wanted the hospital to follow. When he died on December 24, 1873, the hospital was still in its very early planning stages. [23] Above all of this, it must not be forgotten that Johns Hopkins himself enslaved people as late as 1850. [24] To learn more about the complex histories of racism at Johns Hopkins, please explore the Hard Histories at Hopkins Project, led by the brilliant historian Dr. Martha S. Jones.

The story of Henrietta Lacks illuminates patterns of historical migration to Baltimore, the impacts of racial segregation, extensive histories of non-consensual scientific experimentation on African Americans, and the legacies of slavery in the United States. This is a Baltimore story and should be told and remembered as such. Henrietta Lacks left the Virginia lands where her enslaved ancestors worked tobacco fields to come to Baltimore with her family for a better life. When she became ill with cancer, Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore was the only place for her to go. Henrietta remained in Baltimore except to visit her daughter Elsie who was institutionalized at the closest hospital for African American people living with disabilities. [25] She also left Baltimore occasionally to revisit her former home in Virginia and reconnect with her enslaved ancestors. The histories of exploitation of African Americans through the medical system led people in Henrietta’s community to fear that if children wandered around East Baltimore after dark, they would be kidnapped by Johns Hopkins staff. [26] This fear of being non-consensually forced into unjust treatment at Johns Hopkins Hospital reached a measure of reality when this hospital took Henrietta’s cells without asking for her consent. That many major advances in the history of American medical science relied upon Henrietta’s stolen cells only strengthens the argument that African American people built much of the United States, sometimes voluntarily and often not. [27]

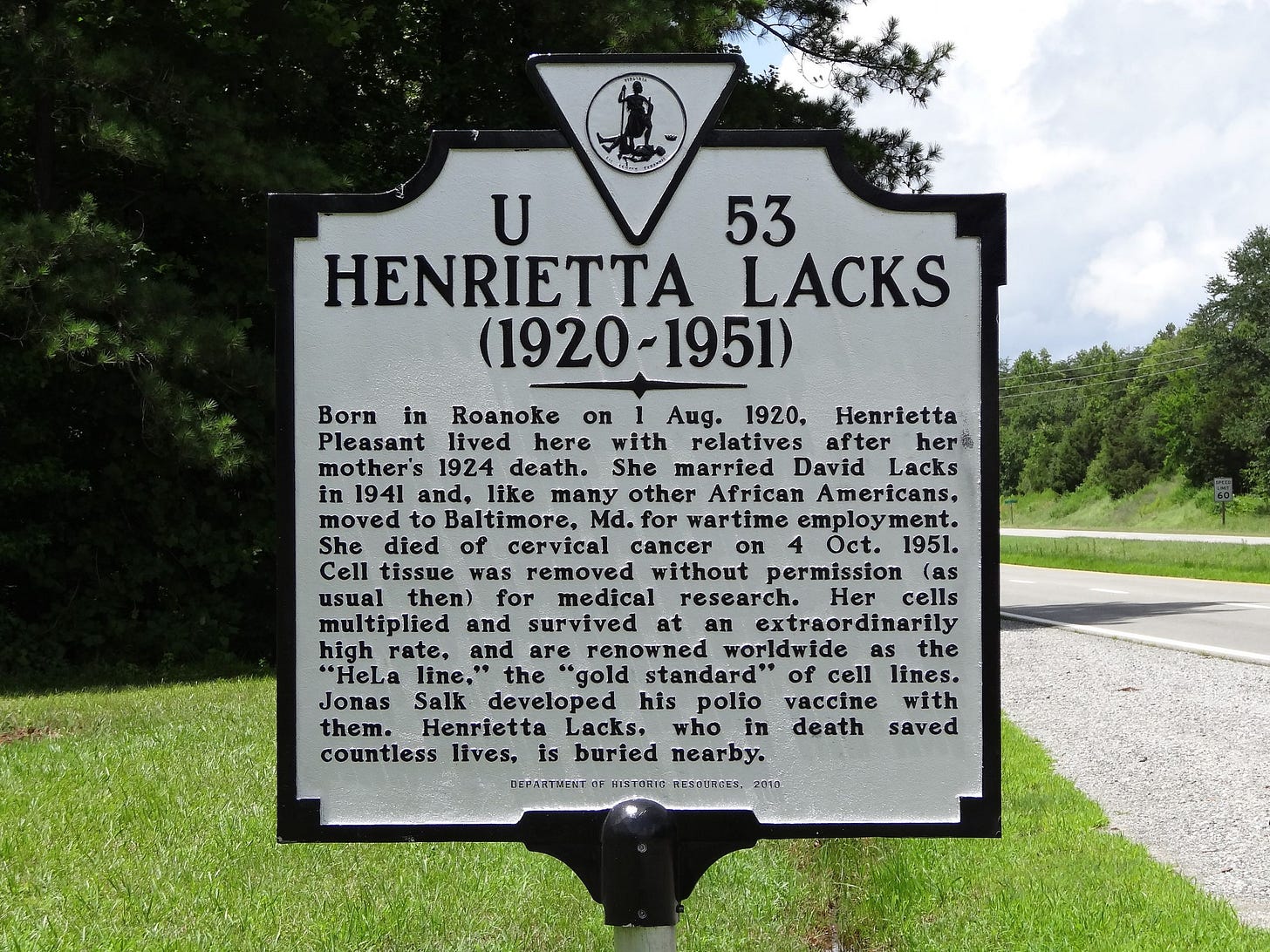

[1] EMW, “Henrietta Lacks historical marker; Clover, VA; 2013-07-14,” photograph (Clover, VA, July 14, 2013), Creative Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Henrietta_Lacks_historical_marker;_Clover,_VA;_2013-07-14.JPG.

[2] Benjamin Butanis, “The Importance of Hela Cells,” Johns Hopkins Medicine, February 18, 2022, https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/henriettalacks/importance-of-hela-cells.html.

[3] Tracie White, “Descendants of Henrietta Lacks Discuss Her Famous Cell Line,” Stanford Medicine News Center, May 2, 2018, https://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2018/05/descendants-of-henrietta-lacks-discuss-her-famous-cell-line.html.

[4] Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (New York: Crown Publishers, 2010), 18, Kindle edition.

[5] Karen Olson, Wives of Steel: Voices of Women from the Sparrows Point Steelmaking Communities (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005), 2-3, https://archive.org/details/wivesofsteelvoic0000olso.

[6] See Ken Jones, “Sparrows Point Shipyard: 100 Years of Shipbuilding,” The Baltimore Museum of Industry, November 11, 2020, https://www.thebmi.org/sparrows-point-shipyard/; Olson, Wives of Steel, 8.

[7] See Olson, Wives of Steel, 2.

[8] Andrew J. Cherlin, “‘GOOD, BETTER, BEST’: Upward Mobility and Loss of Community in a Black Steelworker Neighborhood,” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 17, no. 2 (Fall 2020): 212, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X20000284.

[9] Blair L.M. Kelley, Black Folk: The Roots of the Black Working Class (New York: Liveright, 2023), 14, Kindle edition.

[10] Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, 15.

[11] Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, 30-33.

[12] Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, 93-286.

[13] Michael Gill and Nirmala Erevelles, “The Absent Presence of Elsie Lacks: Hauntings at the Intersection of Race, Class, Gender, and Disability,” African American Review 50, no. 2 (Summer 2017): 123-137, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26444064.

[14] Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, 45.

[15] Gill and Erevelles, “The Absent Presence of Elsie Lacks,” 135.

[16] Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, 83.

[17] Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, 275.

[18] Deirdre Cooper Owens, Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 2017), 14, open access, https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/30659/644220.pdf.

[19] Owens, Medical Bondage, 1.

[20] Vanessa Northington Gamble, “Under the Shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and Health Care,” American Journal of Public Health 87, no. 11 (November 1997): 1773, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1381160/.

[21] Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, 49-50.

[22] Jennifer Schuessler, “Johns Hopkins Reveals That Its Founder Owned Slaves,” New York Times, December 9, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/09/arts/johns-hopkins-slavery-abolitionist.html; Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, 15.

[23] Gert H. Brieger, “THE ORIGINAL PLANS FOR THE JOHNS HOPKINS HOSPITAL AND THEIR HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 39, no. 6 (November-December 1965): 519, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44447602.

[24] Schuessler, “Johns Hopkins Reveals That Its Founder Owned Slaves,” New York Times.

[25] Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, 45.

[26] Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, 165.

[27] For more on this crucial argument, please read Nikole Hannah-Jones, “Preface: Origins,” in The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story, ed. Nikole Hannah-Jones, Caitlin Roper, Ilena Silverman, and Jake Silverstein (New York: One World Books, 2021), xvii-xxxiii.