Druid Hill Pool No. 2: Memorializing the One Public Pool for Black Residents of Segregation-Era Baltimore

BHW 3: February 18, 2023

In Baltimore’s Druid Hill Park today there is a striking memorial to the oppression, racial violence, and lives lost due to the segregation of the city’s municipal swimming pools. It sits on the former site of Druid Hill Park Pool No. 2, the only one of segregation-era Baltimore City’s seven outdoor pools which permitted Black swimmers. According to National Park Service records, this pool was built in 1921 and from its opening “was small for the large number of people it was designed to serve, since it was the city’s only black public pool.” In 1956, the year Baltimore desegregated its municipal swimming pools, Pool No. 2 closed for good. There was no longer much demand for it as its formerly whites-only counterpart across the park was larger, nicer, and now open to all. [1] Pool No. 2 sat abandoned until 1999, when the city commissioned Baltimore-born Black artist Joyce J. Scott to turn it into a memorial. [2] Scott’s design filled the pool basin to ground level with dirt and sod, while maintaining the circumference of the pool with a tiled boundary and depth markings (Figure 1). A pool ladder, diving board, and lifeguard chair are the memorial’s most eye-catching features (Figure 2). These structures ensure the undersized, undermaintained, relatively-inaccessible pool for Black Baltimoreans remains imprinted on the public historical landscape. It serves as a reminder of the city’s harsh, violent history of racial segregation, while also honoring the community-building and Black joy that took place at the pool.

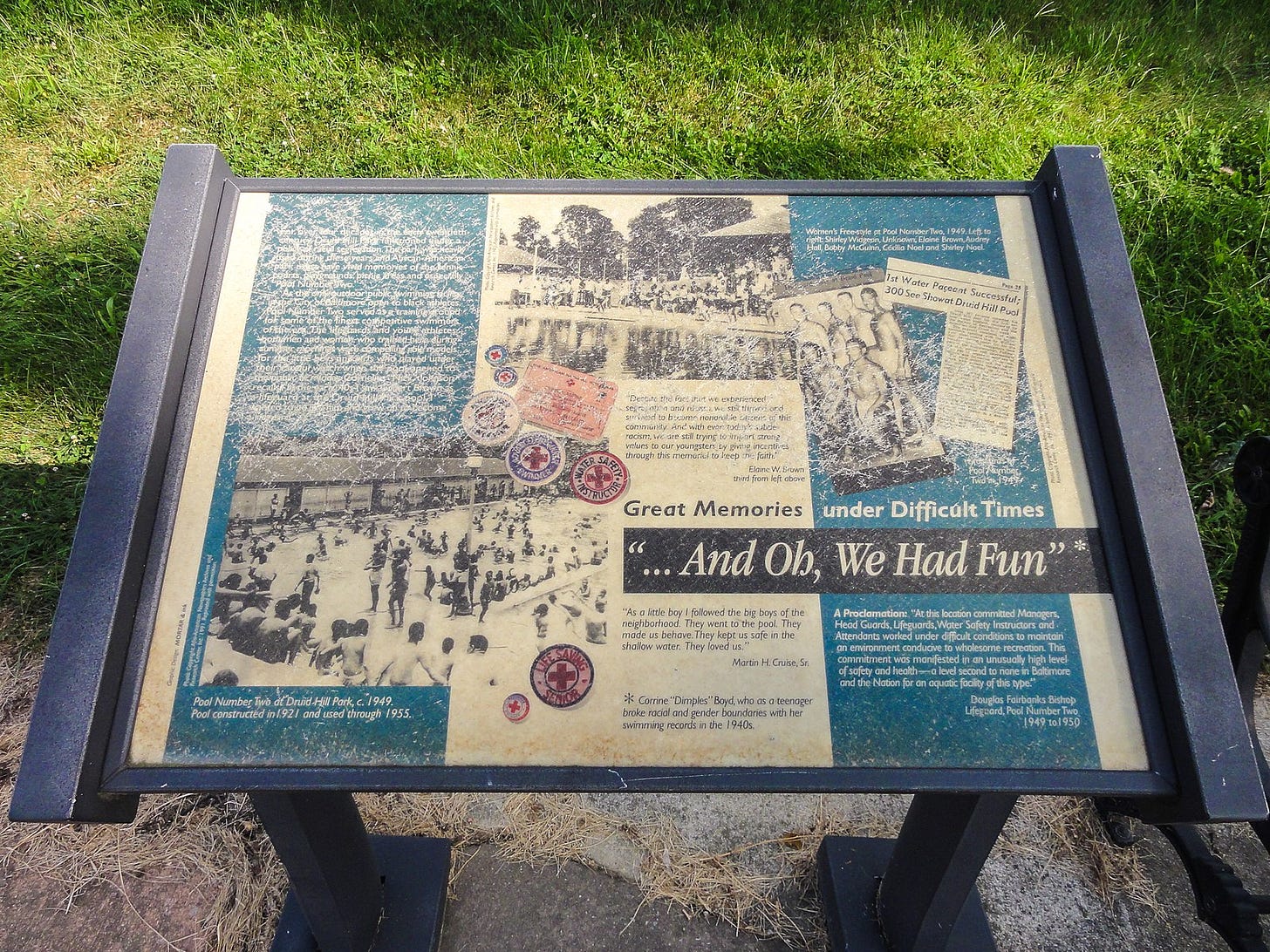

While one interpretive panel describes a positive outlook on the pool’s history as “Great Memories under Difficult Times,” the memorial also commemorates three young Baltimoreans who died from drowning in the summer of 1953 (Figure 3). [5] In this way, it in part memorializes events that happened away from the site due to the pool’s lack of accessibility for Black residents. The first incident took place on July 29, 1953, when 13-year-old Black Baltimorean Thomas Cummings drowned in the Patapsco River where he and four friends were swimming. They lived very close to the whites-only pool in Clifton Park, but they were barred from entering this segregated pool, so they swam in the river instead. When interviewed by the Baltimore Afro-American, Cummings’s mother stated, “I told Tommy to never go swimming unless there were lifeguards around. But he loved the water and I guess there was no place else for him to go.” She continued, “they ought to give our children somewhere to swim before more of them die like Tommy.” [6] While Baltimore’s NAACP and the Park Board tried to address the issue, two more young Black children drowned. Indeed, later that summer on August 18, 7-year-old William Beckett and 8-year-old Charles Rogers died while swimming in a construction site excavation that had filled with rainwater. Their surviving friends told the Afro-American that the group went swimming at this worksite near their homes “rather than hike three miles to the nearest outdoor pool for colored [sic] at Druid Hill park.” [7] The unnamed reporter made clear the connections to the Cummings drowning, writing:

The death of the two boys came close on the heels of a third drowning that occurred near the Hanover street bridge less than a month ago. In each case, victims lost their lives outside of city operated swimming pools. Citizens have urged authorities all summer to admit colored citizens to all Baltimore pools. [8]

These deaths added urgency to the cause of pool desegregation, making it clear that without action to address the issue, Black Baltimoreans would continue to suffer. The mark on the landscape of lives lost to segregation is amplified by the graveyard that is visible behind the pool today. [9]

Swimming pools received an inordinate amount of attention in mid-twentieth century battles over the desegregation of public facilities across the United States. Defenders of segregated pools cited perceived moral and physical threats posed by interracial swimming. Historian Jeff Wiltse examines the moral side of this, arguing that “The visual and physical intimacy that accompanied swimming made municipal pools intensely contested civic spaces.” He claims that the shared water, revealing outfits, and close confines of the public pool experience made white Americans morally uncomfortable with the idea of desegregation. [11] Historian Victoria W. Wolcott emphasizes perceived sexual threats, arguing that interracial swimming “raised the specter of miscegenation” in an era when interracial marriage and sexuality were heavily policed. [12] In addition to these moral concerns, racist views about disease added a physical element of fear. There was a prominent view among white Americans of this era that Black people were more likely to carry and spread disease, a process allegedly accelerated by the sharing of swimming water. [13] Joyce J. Scott, the artist behind the Pool No. 2 memorial, shared some details about these views in a 2009 Smithsonian oral history interview. She stated, “the thing about the colored swimming pool was that it was filtered because they were sure that we had something. But the white swimming pool wasn’t filtered, so they were peeing in the pool and giving people all kinds of diseases.” [14] Regardless of the truth of this story, it speaks to the racial fears that influenced discussions about pool segregation.

Perceived racial threats led to direct violence at Baltimore-area natural swimming holes, which stoked further fears about interracial swimming in any setting. Swimming holes were not segregated, and conflicts at these shared spaces received significant attention in Baltimore newspapers. For example, on August 8, 1953, in between Cummings’s death and the deaths of Beckett and Rogers, the Baltimore Sun reported on fatal violence at one of these sites. According to the report, a white man named E. G. Padgett died after “an argument with a group of Negroes at a Patuxent river swimming hole.” The Sun reported that on his deathbed Padgett told the police “He had been swimming with three friends when a group of Negroes drove up in an automobile and an argument developed.” Allegedly, Padgett was knocked down in the ensuing skirmish and then went home to get his shotgun. When he returned, “he fired twice, but no one was hurt. The fatal beating followed.” Nine people were arrested, seven under murder charges, in this case. The Sun portrayed Padgett as the “victim” in the case, despite him being the one who went to fetch a firearm, thus escalating the situation. [15] This incident provided further fuel for the fire of white resistance against pool desegregation. The underlying white fear was that since deadly violence was occurring at unsegregated swimming holes, surely deadly violence would result from desegregating swimming pools. This violence would likely also put more lives at risk since pools tended to be in dense population centers, as opposed to the typically more rural swimming holes. [16]

Black Americans persistently resisted swimming pool segregation, facing violence as a result. This must not be lost in the nostalgic “And Oh We Had Fun” rhetoric on some of Pool No. 2’s commemorative signage (Figure 3). [17] Wolcott coins the term “recreation riots” to describe the conflicts that ensued when Black Americans attempted to occupy prime public recreational space. [18] In the mid-twentieth century, amidst what some have described as the “golden age” of American recreation, swimming pools were at the top of the list of coveted public spaces. The routine violence and exclusion that resulted from attempts to desegregate these pools make clear that any “golden age” description of this period is naive. [19] Law enforcement’s handling of these pool conflicts disproportionately punished people of color, as evidenced in the Padgett case. In this way, swimming pool violence reflected the broader postwar development of the racialized carceral state. Historian Heather Ann Thompson’s work on “the ‘criminalization of public space’” in the postwar period provides helpful insights for understanding this. As desegregation advanced, shared public spaces increasingly became hubs for racially disproportionate punishment whenever the white social order was threatened. [20] This is part of why after desegregation some pools decided to close entirely rather than open for interracial swimming. These decisions relied on popular assumptions that the risk of violence and even deaths from opening pools to all outweighed the benefits of opening them at all. [21] For the pools that did remain open, racial fears ensured white attendance dropped dramatically. [22]

The multi-faceted nature of Black resistance to pool segregation is remarkable, spanning from the acts of individual children to those of large organizations like the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). This national movement included everyday resistance from youth and ordinary Black consumers alongside CORE’s nonviolent demonstrations, the NAACP’s legal advocacy, and the efforts of the Afro-American newspaper to publicize the cause. [23] These forms of resistance proceeded in unison, with individual protests giving rise to CORE demonstrations which then sparked legal cases. [24] It was ultimately an NAACP lawsuit that legally desegregated Baltimore’s municipal pools through an early-1955 U.S. Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals decision. [25] A notable case of grassroots resistance leading to these wider changes started when 17-year-old Mamie Livingston sent a letter of concern to the Afro-American. The paper published portions of the letter, which proclaimed:

We live near Clifton Park and would like very much to have swimming rights there. Last year on attempting to enter we were turned away with scorn and told our outdoor swimming pool would be built by this summer. As of yet we have heard nothing more of this. If this country is ever going to have equal rights, why not start here? [26]

Livingston’s direct connection of the pool issue to the national civil rights struggle speaks to the 17-year-old’s understanding of the breadth of the movement and the importance of everyday resistance. Relatedly, Wolcott argues that swimming pool desegregation battles showed the resistance of children and teenagers, age groups “often overlooked in our understanding of mid-century civil rights.” [27] Livingston’s letter had a significant impact, resulting in an Afro-American investigation and survey to determine the scope of the pool segregation issue. The paper published the responses, providing further evidence of the unjust situation and generating more momentum for the cause. [28] Ultimately, CORE and the NAACP would turn this momentum into nationwide legal change.

In the 1950s, Black Baltimoreans asserted and won legal rights to occupy and enjoy public swimming pools and other desirable public spaces. Desegregation of public facilities brought legal equality of access to urban environments, but white supremacy and systemic racism continued to find ways of enforcing segregation through privatization or closure. [29] When Pool No. 2 sat abandoned from 1956 to 1999, the space it occupied did not receive public historical respect. Instead, Druid Hill Park’s Zoo used its facilities for storage. [30] Meanwhile, Druid Hill Park itself has long-contained numerous memorials to famous white men, including George Washington, Christopher Columbus, Richard Wagner, and William Wallace. The Park to this day lacks any statues of Black historical figures. [31] However, the pool memorial inextricably demonstrates respect and acknowledgement of the great significance of Black history and community strength in Baltimore. Its unveiling reclaimed this space for the lived experiences of those who smiled and swam in this pool. But Pool No. 2 memorializes much more than positive nostalgic memories. The Sun got this very wrong in the early stages of the memorial’s development, evidenced by its headline proclaiming, “Many Blacks [sic] Nostalgic for the Segregated Druid Hill Park.” [32] While it does commemorate the joy, friendships, and family fun Black Baltimoreans experienced at the pool, it also crucially embodies the traumas, violence, and deaths caused by recreational segregation. In addition to warm nostalgia, the memorial also reflects extreme collective pain. The understated nature of the poolside structures encourages viewers to contemplate and process this complex historical space. It thus stands as an instructive example of how difficult histories can be memorialized in a way that encourages introspection, conversation, learning, and remembrance.

[1] Elizabeth Jo Lampl, “Druid Hill Park, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form,” June 1997, United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 44, https://mht.maryland.gov/secure/medusa/PDF/NR_PDFs/NR-167.pdf.

[2] Explore Baltimore Heritage, “Druid Hill Park Pool No. 2: Memorial Pool Recalling Swimming during Segregation,” Baltimore Heritage, n.d., https://explore.baltimoreheritage.org/items/show/500; Jaime Schultz, “Lest We Forget: Public History and Racial Segregation in Baltimore’s Druid Hill Park,” in Representing the Sporting Past in Museums and Halls of Fame, ed. Murray G. Phillips (New York: Routledge, 2012), 379, Kindle edition.

[3] Graham Coreil-Allen, “Druid Hill Park Memorial Pool Edge Tiles Detail,” photograph, Wikimedia Commons (Baltimore, March 27, 2020), https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Druid_Hill_Park_Memorial_Pool_edge_tiles_detail.jpg.

[4] Graham Coreil-Allen, “Druid Hill Park Memorial Pool Diving Board Stand,” photograph, Wikimedia Commons (Baltimore, March 27, 2020), https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Druid_Hill_Park_Memorial_Pool_diving_board_stand.jpg.

[5] Graham Coreil-Allen, “Druid Hill Park Memorial Pool Historical Sign,” photograph, Wikimedia Commons (Baltimore, March 27, 2020), https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Druid_Hill_Park_Memorial_Pool_historical_sign.jpg.

[6] Buddy Lonesome, “Boy, 13, drowns for lack of pool,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 1, 1953, https://news.google.com/newspapers/p/afro?nid=JkxM1axsR-IC&dat=19530801&printsec=frontpage&hl=en.

[7] “BURY TWO DROWNED BOYS, 20 workers in area as boys drown,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 22, 1953, 1, https://news.google.com/newspapers/p/afro?nid=JkxM1axsR-IC&dat=19530822&printsec=frontpage&hl=en.

[8] “BURY TWO DROWNED BOYS,” August 22, 1953, 31.

[9] Schultz, “Lest We Forget,” 379.

[10] Coreil-Allen, “Druid Hill Park Memorial Pool Historical Sign.”

[11] Jeff Wiltse, Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 2-3, 84-85, https://archive.org/details/contestedwaterss0000wilt.

[12] Victoria W. Wolcott, Race, Riots, and Roller Coasters: The Struggle over Segregated Recreation in America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), 16, Kindle edition.

[13] Wolcott, Race, Riots, and Roller Coasters, 19, 63.

[14] “Oral history interview with Joyce J. Scott,” July 22, 2009, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-joyce-j-scott-15711.

[15] “7 ARE CHARGED WITH MURDER,” Baltimore Sun, August 8, 1953, 12, https://www.newspapers.com/clip/118613886/the-baltimore-sun/.

[16] Wiltse, Contested Waters, 146.

[17] Coreil-Allen, “Druid Hill Park Memorial Pool Historical Sign.”

[18] Wolcott, Race, Riots, and Roller Coasters, 4, 7.

[19] Wolcott, Race, Riots, and Roller Coasters, 11-12.

[20] Heather Ann Thompson, “Why Mass Incarceration Matters: Rethinking Crisis, Decline, and Transformation in Postwar American History,” The Journal of American History 97, no. 3 (December 2010): 706, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40959940.

[21] Wolcott, Race, Riots, and Roller Coasters, 72.

[22] Wiltse, Contested Waters, 157.

[23] Karen Olson, “Old West Baltimore: Segregation, African-American Culture, and the Struggle for Equality,” in The Baltimore Book: New Views of Local History, ed. Elizabeth Free, Linda Shopes, and Linda Zeidman (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991), 67, https://archive.org/details/baltimorebooknew0000unse.

[24] Wolcott, Race, Riots, and Roller Coasters, 3-4, 74.

[25] Explore Baltimore Heritage, “Druid Hill Park Pool No. 2”; Wolcott, Race, Riots, and Roller Coasters, 116.

[26] “Closed Gates of City Pools Drawing Mounting Protests,” Baltimore Afro-American, July 18, 1953, 3, https://news.google.com/newspapers/p/afro?nid=JkxM1axsR-IC&dat=19530718&printsec=frontpage&hl=en.

[27] Wolcott, Race, Riots, and Roller Coasters, 86-87.

[28] “Closed Gates of City Pools,” July 18, 1953, 3.

[29] Wolcott, Race, Riots, and Roller Coasters, 13.

[30] Lampl, “Druid Hill Park,” 16.

[31] Schultz, “Lest We Forget,” 381.

[32] Rafael Alvarez, “Fond memories of a harsh era 'Sacred' sites: Many blacks are nostalgic for the segregated Druid Hill Park of years gone by, and the plan to renew the park will include a memorial to that era,” Baltimore Sun, April 13, 1996, https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1996-04-13-1996104036-story.html.

But yeah I'm looking forward to being the dumbest person in this group. decentralized sports betting platform for crypto folks - https://tinyurl.com/3fbhv4ts