In early July 1877, the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) Railroad Company announced it was reducing worker wages by ten percent effective July 16. [2] The United States was facing an economic depression, due substantially to the over-expansion of national railroad systems. [3] This was not the first time the company slashed wages that year, nor was it the only railroad company lowering its pay. But it was this set of wage cuts that ignited a strike, followed by a riot, that became the first national strike in American history. At Baltimore’s Camden Junction on July 16, a group of B&O workers stopped working and asserted they would not resume work until the new cuts were rescinded. [4] Company executives responded by utilizing their sway over government decisionmakers, ordering in state and federal troops to crush the strike. Many Baltimoreans took issue with this strikebreaking military incursion into their city. Discontent escalated into deadly mass violence on July 20, resulting in at least ten deaths. This combination of striking B&O workers and public violence in Baltimore fueled the spread of further labor demonstrations across the country in what became known as the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. While most of the Baltimoreans arrested for rioting were not directly affiliated with the striking workers, their public unrest embodied solidarity with the labor demonstrators. [5] Such solidarity empowered the strike’s national spread. This story also demonstrates the remarkable power and influence of B&O executives in the late-nineteenth century, as well as the limits of this power.

Numerous scholars emphasize that the Baltimoreans rioting in the streets in July 1877 did not themselves work for the B&O and thus operated separately from the strikers, but this is not entirely true. [6] At least three Baltimorean B&O strikers were arrested on charges of threatening a riot on July 16, the day the strike began. These charges were deferred, perhaps reflecting a lack of evidential support. [7] In the days that followed, most rioters escalating the conflict were not directly associated with the B&O. Nevertheless, these public agitators mostly shared working class identity with the strikers. Workers in non-railroad Baltimore industries such as canning and box making also dealt with the repercussions of national economic struggles in the 1870s. Frustration with wages and working conditions across industries likely provided significant motivation for the public violence that July. With its concerted attacks on troops mustering to suppress striking workers, the mob expressed collective discontent with the strikers through its actions. [8]

It is difficult to reconstruct the identities of the Baltimoreans who rioted as part of the Great Strike of 1877. While they were mostly working class, there was significant cross-class support from middle-class Baltimoreans. The crowd was primarily white people. [9] This is particularly notable since the construction of the B&O’s Camden Station, where much of the violence took place, forcibly displaced Black Baltimorean communities. The mob’s whiteness further contributed to the local Black exclusion wrought by this displacement by placing white empowerment at the center of the struggle narrative. [10] Additionally, it appears that women, specifically working-class women, made up a significant portion of the group. [11] The relative uncertainty about participant identities extends beyond the rioters, also applying to the B&O strikers. What is clear is that the railroad industry was predominantly white at this time. Reports indicated workers congregating and grumbling about the latest wage cuts, but there was not a collectively planned effort to organize a strike. [12] Indeed, the resistance’s grassroots character further masks the identities of the strikers. Like the crowd in the streets, not a lot is known about the strikers other than that they were largely white, working-class Baltimoreans.

As violence escalated in the streets of Baltimore on July 20 and 21, key decisionmakers from both the city government and the B&O congregated together in the B&O offices at Camden Station. [13] While the rioters appeared to be on the side of the strikers, municipal leadership was clearly on the side of the B&O. This reflects the great power the company wielded over local authorities. Baltimore City and the State of Maryland were primary investors in the company, providing direct financial motivation for government leaders to support B&O strikebreaking. [14] When B&O executives requested military assistance to crush the strikers, state and municipal leaders swiftly complied. In ringing out the militia mobilization call on the evening of July 20, Maryland National Guard leader General James Herbert aimed to protect the interests of the B&O. As historian Dennis P. Halpin emphasizes, “For Baltimoreans, the ringing of the bell signaled the government’s intention to not only protect the B&O but to do so at the expense of laborers.” [15] Some rioters may have been more interested in taking out their social frustrations with the government establishment than engaging directly with the labor movement, but struggling against these anti-worker forces showed solidarity nonetheless. The B&O and the military provided a common adversary representative of oppressive power structures built into the capitalist economy of the United States.

The deployment of Baltimore City police forces as special strike-crushing railway constables at Camden Junction, just outside of Baltimore City jurisdiction, exemplifies the power of B&O leaders. Throughout the 1877 strikes and violence, company leaders demonstrated unabashed confidence in their own power and influence. [16] Camden Junction was technically in Howard County at the time, it was not part of Baltimore City. When B&O workers started striking, company leaders ordered a strong police response. Baltimore City Mayor Ferdinand Latrobe directly supported the ensuing law enforcement action, exemplifying how city officials operated at the whims of B&O executives. A Howard County judge attempted to rule that Baltimore City police could not be employed at Camden Junction since it was outside their jurisdiction. In response, B&O leaders cited vague charter rights as the basis for commissioning Baltimore City police officers as a special railway police force. [17] It appears that the company’s capital-backed sociopolitical strength overpowered the jurisdictional distinctions of local government in this case. The B&O claimed that it possessed broad rights to create its own special forces not subject to jurisdictional limits. This was not met with substantial authoritative resistance. To the contrary, the city’s police commissioners were among the decision-makers gathered in Camden Station as the strikes and riots unfolded. [18] Like the political leaders they congregated with, their literal presence in the B&O headquarters reflected the company’s great influence over them. When the Baltimore police went to work arresting Baltimoreans for taking part in the July 20 and 21 public violence, they did so to a significant extent as an extension of the B&O. [19]

To understand the impacts of the Great Strike of 1877, it is important to establish the prominence of railroads in the economy of the late-nineteenth century United States. As historian Michael A. Bellesiles succinctly summarizes: “The key to America’s industrialization, the railroads were the nation’s largest enterprise—with the most workers and the highest capitalization—and the primary form of transportation.” [20] This meant that despite being treated poorly by their employers, railroad workers were collectively the most powerful workers in the country. No other industry possessed comparable ability to bring the national economy to a halt. By striking, railroad workers made clear their awareness of the leverage they possessed. While clear labor victories from the 1877 strikes were sparse, workers at the very least gained a new understanding of their place in the national labor market. [21] When rail companies fired strikers and quickly hired replacements, people surely took note. The company’s reputation for such disreputable practices further explains the popular outrage against the B&O and its government backers that fueled escalating violence.

In mid-July 1877, Baltimorean B&O workers went on strike and the city’s working population rallied around them. Some middle-class Baltimoreans joined in solidarity. Mass violence ensued as Baltimoreans violently resisted B&O efforts to harness government authority to crush the strike. These events inspired a wave of railroad strikes across the United States, which resisted the state-backed capitalist exploitation of the working class in the midst of a national economic downturn. By the end of the fourth day of the strike, July 19, the Great Strike of 1877 had spread from Baltimore to Chicago with many offshoots in between. [22] B&O workers at Camden Junction deemed the latest wage cuts unacceptable, channelling discontent into public outrage. They stopped working and ignited a movement. The Camden Junction and surrounding Camden Yards areas are thus significant sites of American labor history. However, this history is not prominently featured in the sports complex that covers the Camden Yards area today. While its industrial theme creates memorable sporting event experiences, the entertainment district also appropriates these histories without sufficiently acknowledging their importance. [23] The historical marker at the site today is a good start. As it proclaims: “THE STRIKE ENERGIZED THE LABOR MOVEMENT.” [24] It also did so in a distinctly Baltimorean setting, making a Baltimorean statement about rights for workers that reverberated across the United States. This story necessitates greater public emphasis on Camden Yards as a place of working-class resistance and solidarity in the face of corporate-government oppression in Baltimore City.

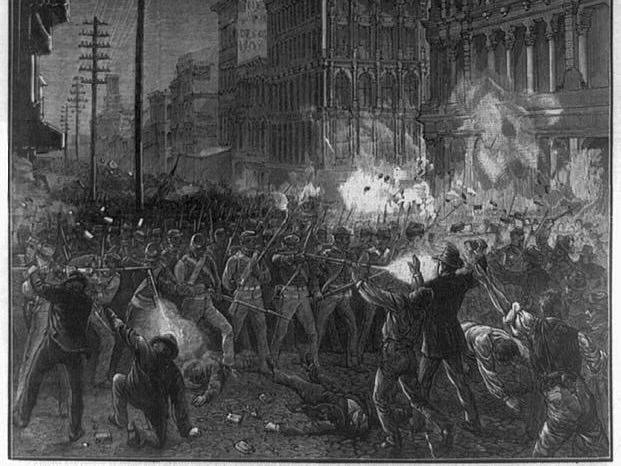

[1] “The Great strike—the Sixth Maryland Regiment fighting its way through Baltimore, from a p[hotogr]aph by D. Bendann,” Harper’s Weekly (New York, NY), August 11, 1877, https://www.loc.gov/resource/cph.3b45187/.

[2] J. A. Dacus, Annals of the Great Strikes in the United States (Chicago: L. T. Palmer & Co., 1877), 27, https://www.loc.gov/item/08000146/.

[3] David Schley, Steam City: Railroads, Urban Space, and Corporate Capitalism in Nineteenth-Century Baltimore (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2020), 201, Kindle edition.

[4] Dacus, Annals of the Great Strikes, 28-30.

[5] Michael A. Bellesiles, 1877: America’s Year of Living Violently (New York: The New Press, 2010), 152, https://archive.org/details/1877americasyear0000bell.

[6] See Dennis P. Halpin, “Reforming Charm City: Grassroots Activism, Politics, and the Making of Modern Baltimore, 1877-1920” (PhD diss., Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 2012), 49, https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/38793/pdf/1/; Philip S. Foner, The Great Labor Uprising of 1877 (New York: Pathfinder, 1977), 49, https://archive.org/details/greatlaboruprisi0000fone.

[7] Clifton K. Yearley, Jr., “The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Strike of 1877,” Maryland Historical Magazine 51, no. 3 (September 1956): 193, https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc2200/sc2221/000009/000008/pdf/14287001.pdf.

[8]John F. Stover, History of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 1987), 138-139, https://archive.org/details/historyofbaltimo0000stov.

[9] Halpin, “Reforming Charm City,” 30.

[10] Schley, Steam City, 124.

[11] Dacus, Annals of the Great Strikes, 67-68.

[12] Dacus, Annals of the Great Strikes, 27-28.

[13] Yearley, Jr., “The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Strike of 1877,” 204.

[14] Mary P. Ryan, Taking the Land to Make the City: A Bicoastal History of North America (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2019), 219, Kindle edition.

[15] Halpin, “Reforming Charm City,” 27.

[16] Yearley, Jr., “The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Strike of 1877,” 195.

[17] Yearley, Jr., “The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Strike of 1877,” 193.

[18] Sander, John W. Garrett, 428.

[19] Foner, The Great Labor Uprising of 1877, 49.

[20] Bellesiles, 1877: America’s Year of Living Violently, 146.

[21] Sylvia Gillett, “Camden Yards and the Strike of 1877,” in The Baltimore Book: New Views of Local History, eds. Elizabeth Fee, Linda Shopes, and Linda Zeidman (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991), 11, https://archive.org/details/baltimorebooknew0000unse.

[22] Dacus, Annals of the Great Strikes, 54-55.

[23] Gillett, “Camden Yards and the Strike of 1877,” 14.

[24] Beverly Pfingston, “Great Railroad Strike of 1877 Marker,” photograph (Baltimore, MD, March 23, 2013), https://www.hmdb.org/PhotoFullSize.asp?PhotoID=236682.